Medieval Dunstable© Webmaster Helen Mortimer Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

MEDIEVAL TOURNAMENTS IN DUNSTABLE

By John Buckledee

Chairman, Dunstable and District Local History Society

Former Editor of the Dunstable Gazette

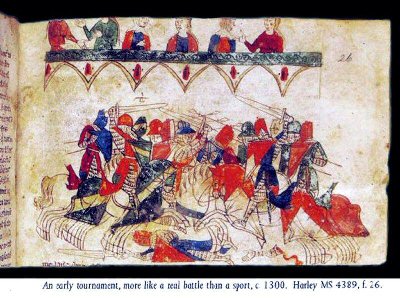

Dunstable was one of England’s main centres for knightly tournaments in early medieval times. These were massive affairs – mêlées – with hundreds of armoured horsemen taking part in mock battles over a large area.

Mêlées should not be confused with jousting - hugely popular in later centuries - which featured two mounted knights with lowered lances charging each other in single combat.

Heralds Sound The Advance. A painting by Hugh St Pierre Bunbury published by the Boys Own Paper in January 1914.

Dunstable tournaments are mentioned in numerous documents, not least the Annals of Dunstable – the diary kept by the canons of Dunstable Priory. And there are many records of Dunstable tournaments being banned by the king, with men being despatched by him to enforce his orders. No king, struggling to keep control of his realm, wanted to give powerful barons an excuse to bring their private armies from all parts of the country to assemble in Dunstable - just 30 miles from London.

Where were the tournaments held? No-one really knows, but the ideal sites would have been the lower slopes of the downs on the south and west of the town. It is only in recent years that houses have encroached upon these grassy areas, once kept trim by flocks of sheep. The fields stretched from Luton, across Skimpot and the foot of Blow’s Downs, along what is now the Manshead School campus and the Oldhill estate, across what is now the golf course and into the Meadway area alongside West Street. It was ideal galloping country, well drained and with no crops to be disturbed.

Mêlée organisers would have divided the “armies” into two separate settlements, with the tournament taking place over the land between the two bases. The battle would begin with a massed charge in front of stands erected for spectators. The warhorses galloped in extended lines so that any knight toppled by a lance would not be severely injured by falling into the path of others. The fight would then spread out into numerous running battles, with knights seeking to capture opponents or their horses and hold them to ransom. It would continue until everyone was exhausted or night fell.

Tournaments on the Continent were well established before they were allowed in England, and were much bigger affairs. They took place over several square miles, with individual battles sometimes continuing beyond the view of most spectators.

The Dunstable events, although smaller in scale, would nevertheless have covered a considerable area. The Dunstable tournament in 1309, about which many details have survived, had around 250 knights taking part and that number of galloping horses would have needed a lot of space. The drama of today’s Grand National, with a mere 40 horses, would have been trivial by comparison.

Descriptions of tournaments on the Continent give us a flavour of what might have been seen in Dunstable.

The two opposing armies would charge at each other as trumpets and horns sounded and battle cries were shouted. There would be a loud crash as the lines of horses collided and lances splintered. Some riders would be unhorsed (Duke Geoffrey, the son of Henry II of England, was trampled to death at a tourney near Paris) and uninjured knights would continue fighting on foot.

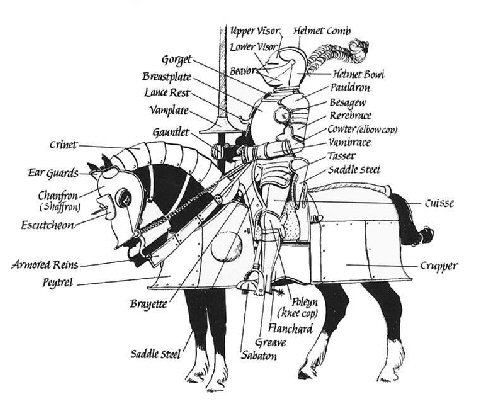

It was a violent and dangerous sport, even though their swords were blunt, their spears unpointed, and they wore heavy armour.

David Crouch, in his book “Tournament”, describes the scene at a Continental mêlée: “The knights who did not go down, but passed through the opposition, rapidly turned their horses to engage their rivals again….Eventually the struggling mass of horses and riders would break up…Knights could take additional lances held by their squires at the nearby lists and attempt to find the space to charge down another opponent if they could…

“As individual riders took off across the field, with others in pursuit, the mêlée itself fragmented and very soon the people in the stands at the lists would have seen only isolated knots of knights moving across the landscape into the distance.”

Professor Crouch mentions one Continental melee, in 1179, when the tourneyers spread across meadows and woodland and the fight continued across ditches and through woods, with barns acting as temporary forts.

Medieval documents contain numerous references to Dunstable tournaments but unfortunately descriptions are sparse. The best identifiable example of an English tournament site is at Langwith Common, near York. In 1270 this covered 500 acres. For an idea of the size, compare this with today’s huge park around Luton Hoo, which measures 1,000 acres.

Battle reenactment

Whether the area of the Dunstable tournaments was as big as Langwith is not known. It might have been even bigger. Langwith was just outside York, which would have been large enough to house many of the knights and their followers who could have ridden out to the battlefield in the morning. Dunstable would not have had so many houses, so tented villages would have been erected on the downs. And Dunstable’s open land would have been better for spectators: the Langwith site contained much woodland and the battle, after the initial charge, could sometimes only be glimpsed through the trees. At Dunstable the “common folk” would have been able to watch from the hillsides.

The St Albans annalist Matthew Paris recorded that one tournament was arranged for an area between Luton and Dunstable, which seems to indicate a plan to base the two competing armies in either town. With no other evidence available, Professor Crouch makes the educated guess that the venue for this particular tournament was a triangle of land between Luton, Caddington and Dunstable. But in the end this event never took place – the king banned it. And other sites closer to Dunstable could have been used in other years.

Dunno, the Dunstable historian, excitedly reported the discovery of military spurs when Mill Field alongside West Street was ploughed in 1818. Was this the site of the old tournaments, he asked? Well, it could have been the place where the blacksmiths and armourers serving one of the private armies were based. There would have been tents either side of the mêlée area accommodating the knights, their retinues, kinfolk, grooms, servants, cooks, blacksmiths and armourers. There would have been minstrels, jugglers, jesters, conjurers and acrobats.

One estimate is that every knight would have had a “back-up” team of around ten, so in 1309 we could be talking about 2,500 people arriving in town, in addition to any spectators. Perhaps the earlier tournaments were larger – but no details of numbers have survived.

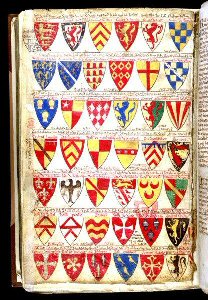

What we DO have at Dunstable is, remarkably, the names of the men who took part in two great Dunstable tournaments in 1309 and 1334.

Such lists, giving details of the heraldic emblems carried by each knight, were prepared for every tournament so each individual, otherwise unrecognisable in his armour, could be identified and some kind of rule could be enforced. Nationally, very few of these lists have survived, so Dunstable is particularly lucky to have copies of TWO.

Scholars have studied the Dunstable tournament rolls in considerable detail, and it is possible to follow the violent and adventurous careers of most of the famous men who fought here.

But tournaments had been held in Dunstable for many years before these surviving lists were prepared. Possibly some were held here during the reigns of Henry I (1100-1135) and Stephen (1135-1154). But Henry II (1154-1189) prohibited them throughout his kingdom at the beginning of his reign and they were not held in England for 40 years.

The Annals of Dunstable, started at the Priory in 1200, make their first reference to a tournament in 1215 when the death of Geoffrey de Mandeville is recorded. He had been fighting a duel at a tournament (not in Dunstable)

King Henry III (1216-1272), whose continual disputes with his powerful brother-in-law Simon de Montford are well documented, banned many tournaments. He was understandably reluctant to give his enemies a legitimate excuse to travel across the country with their private armies and then assemble and compare grievances.

The Annals of Dunstable in 1220 record a decree threatening excommunication for jousters, their managers and supporters, as well as anyone providing them with materials or food. But in 1232 the king relaxed a little and granted permission for four tournament sites in England - in Dunstable, Brackley, Stamford and Blyth - thus adding Dunstable to a small list of venues licensed by King Richard I in 1194. Richard had imposed strict conditions, enforced by three trusted earls, and knights taking part had to pay various fees to the Crown according to their standing.

Why Dunstable? Probably the town’s position on the crossroads of the two great highways, the Watling Street and the Icknield Way, was a consideration. With knights travelling to the tournaments from all over the country it would have been helpful if the directions could be easily followed and if food and drink were available to buy along the way.

Undoubtedly it was important that the mêlées took place over land which was not being used to grow crops. It seems that people living near some of the earlier tournament venues were very unimpressed by the food shortages which sometimes followed.

Dunstable, too, had royal connections – it was, after all, the creation of Henry I who had built the Priory near his “palace” or hunting lodge and then encouraged a town to spring up around it. The town could provide accommodation fit for a king as well as warm rooms for travellers who didn’t relish sleeping in a tent (there exists a document detailing the cost of nails and whitewash to improve cottages for a Dunstable tournament in 1329). Dunstable had bakers and butchers who could provide food for all these extra people. There would have been stores of wine and barrels of ale, essential in times when clean water could be scarce.

But the ordinary townspeople might have had mixed feelings at being selected to host these events. Some folk could have made money but a lot of disruption would have been caused, not only by damage to crops but also by the arrival of hundreds of armed and boisterous young men.

The thrill of the tournament became addictive to the warriors who took part, and many became wealthy from the ransoms paid whenever knights or their horses were captured. They travelled from tournament to tournament and revelled in their fame and their roaming, adventurous life.

William Marshal of England, eventually one of the most trusted and influential men in England (he acted as regent of the country for the boy-king Henry III), was so successful as a tournament fighter on the Continent that his exploits were recounted in a biography.written in around 1224. In one halcyon 10-month period he and his partner-at-arms captured over 100 knights, worth a fortune in ransoms. But it was tough. On one occasion William was due to be awarded a special gift in recognition of his exploits. He missed the ceremony and was eventually found lying with his head on an anvil while armourers used hammers and pincers to extricate him from his battered helmet. It proved, at least, that he had been in the thick of the fight.

The Dunstable Annals of 1260 and 1262 record that Prince Edward of England lost all his horses and money and was so badly bruised in Continental tournaments that he took months to recuperate. And Count Philip of Flanders notoriously learned to make money without actually breaking the rules by lingering on the sidelines until most of the knights were exhausted. He then moved in for easy prey.

William Marshal was particularly skilful at grabbing the reins from an opponent and making it impossible for him to control his horse. Groups of knights would gang up on an isolated opponent, batter him into submission and then share the proceeds. Experienced warriors would watch the preliminary jousting and make a note of which knights were particularly inexperienced and easily captured.

The great nobles, whose ransoms would be large, were tempting targets, but they made sure that they were surrounded by formidable retinues of bodyguards.

There’s an entry in the Catalogue of Ancient Deeds (Vol IV page 15 A6244) which perhaps refers to payment of a ransom, whereby Sir Hugh le Despenser received money from Robert de Clifford and Henry de Grei for two horses at Dunstable and Guildford. (Odiham, Monday after St Martin, 32 Edward (I)).

Prince Edward’s father, King Henry III, prohibited a tournament arranged for Dunstable in the summer of 1245. A great number of barons and knights had assembled at Dunstable and Luton, but the king guessed that the proposed tournament was a ruse to take action against Master Martin, the Pope’s representative in England, whose over-zealous use of his position had made him particularly unpopular.

Despite the ban, the barons demonstrated their power by sending a Bedfordshire knight, Sir Fulk Fitzwarren of Odell and Bramblehanger, to order Master Martin to instantly quit the kingdom. Sir Fulk was perhaps the same knight who had been excommunicated by Pope Innocent III for taking part in a tournament at Stamford in 1216.

The baron’s message was delivered so forcefully that (says Matthew Paris) Martin was terrified and rushed to King Henry for safe conduct. The exasperated king is said to have replied: “The devil give you a safe conduct to hell!”. Nuncio Martin was, nevertheless escorted unharmed back to Italy.

Two years later another tournament was due to be held on land between Luton and Dunstable, resulting from a challenge by the Earl of Gloucester to the king’s half-brother, Guy de Lusignan. The tournament was forbidden, wrote Matthew Paris, as it was feared that Guy and his followers might be massacred, so intense was the feeling against foreign hangers-on at the court.

The king on May 1 1248 prohibited a tournament arranged for “this Tuesday” at Dunstable. The king made his order clear: “If any disobey this prohibition the king will take hold of them so heavily that they and their heirs will feel aggrieved for ever.” (Calendar of Patent Rolls Vol 4 Pg 30).

There’s a description by Matthew Paris of a tournament held in Brackley in 1249 which would have been similar to events in Dunstable except that it became badly out of control.

Paris wrote: “Many of the soldiers from all over the kingdom, who wanted to be called ‘the bachelors’, were asked to take part. In fact on this occasion, even Count Richard of Gloucester who always arranged tournaments between strangers and the local people, whom he supported, enrolled a stranger on his side. In doing so he caused confusion by having the different parts of England represented on the same side, causing enormous damage to his reputation and honour. In this conflict William de Valence, brother of the king, prevailed against the said earl, giving ill treatment to William de Odinges, a very strong soldier, who had joined ‘the bachelors’

“In the same year, at Rochester,... a very significant tournament took place between the English and the foreigners. In this case the foreigners were defeated and they fled ignominiously to their city of refuge…They rearmed and regrouped and hostilities continued. In this way the injuries inflicted in the Brackley tournament were repaid with much interest. As a result, the anger and hatred between the English and the foreign-born continued to increase enormously.”

There were further prohibitions of tournaments planned for Dunstable before Christmas in 1255 and in June 1257, when the king commanded the prior of Dunstable to stop the event. In November 1258 the king prohibited a tournament in Dunstable because, he said, he needed his knights to be ready to put down a rebellion by Llyewelin, son of Grifin.

The Victoria County History records famous confrontations in Dunstable in 1265. The Earl of Gloucester was indignant about the growing power of Simon de Montford and it was in Dunstable that the two men became mortal enemies.

Looking for “matter of revenge” Gloucester had announced a tournament at Dunstable, at which he and Henry de Montford, Simon’s son, were to captain the rival sides. On February 17 1265 Gloucester arrived at Dunstable at the head of a strong band of marchers and others who agreed with him on his opposition to Earl Simon. But the king looked upon such meetings as “nurseries of discord” and the tournament was forbidden. The king wrote to the Prior of Dunstable to see that the ban was carried out.

Gloucester refused obedience and threatened to fight despite the prohibition. But Simon de Montford and Hugh Despenser arrived at Dunstable with a strong force and insisted that the tournament should not take place. There was great disappointment, much murmuring, and Gloucester left in anger, henceforth to be de Montford’s implacable foe.

The king’s struggles against the barons came to a climax that year when he and his son Edward were taken prisoner and Simon de Montford became, in effect, the ruler of England. But Prince Edward escaped, mustered an army, and surprised and killed de Montford. King Henry was restored to power.

When the Prince became king (Edward I) in 1272 he maintained order with an iron hand. He was addicted to tournaments, having fought in numerous mêlées on the continent, and one result was that Dunstable was allowed to become, once again, a centre for these giant events. Accommodation was built for the king at the Priory, next to the Prior’s chamber, and mêlées were held in Dunstable in 1273, 1274, 1279, 1280, 1289, 1292, 1293 and 1301 ( a tournament planned for January 1290 had to be abandoned).

Patrick McGoohan as King Edward I in the film Braveheart.

It’s interesting that there was no question of the king staying at the old royal palace at Kingsbury. King John had given this to the Priory in 1210 and the documentation referring to the gift implies that the building was already derelict and the site had been cleared.

The Annals of Dunstable record that the tournament on Ash Wednesday in 1292 was “hard fought”. There’s a significant entry on this date recording new rules banning grooms or anyone else on foot from carrying a weapon at a tournament except a small shield to protect themselves from the horses. These were formidable animals. Paul Brown’s History of Leighton Buzzard records an incident in 1309 when Philip de Wavendon, while on the king’s service guarding one of his horses at Grovebury, “lost an ear by its bite”.

Despite the additional safety rules, an armour-bearer was killed at the Dunstable tournament in April 1293 and was buried in Dunstable. The fatality is mentioned in the Priory’s Annals but unfortunately the name of the dead man was not recorded.

Interestingly, among those present at the tournament were Prince Edward (later King Edward II), and his cousin Thomas, later Earl of Lancaster, who was to become his bitter enemy. They were close friends at the time (Letters of Edward Prince of Wales, 1304-5, Roxburge Club, Cambridge, 1931).

The 1293 entry is the only time in the Dunstable Annals that there is any mention of death or injury in a Dunstable tournament, although the annalists were quite eccentric in what they did or did not record. There must have been injuries during these violent events. The great lords would have brought their own medical attendants with them, but we can assume that the Priory canons had to use their medical skills as well.

Among many examples of casualties at nearby tournaments is the case of William Melksop, who was pardoned in 1318 for killing William de Pouton at a tournament in Luton; and a particularly violent event at Hertford in 1241 when the loss of life included two eminent figures, Gilbert Marshal and Robert de Say. There was an assassination at a Croydon tournament in 1286 when Sir William de Warenne, son of the Earl of Surrey and Sussex, was ambushed and murdered.

The last regular entry in the Annals of Dunstable is in 1297 when the warlike Edward I was still on the throne. So, apart from the occasional addition, the Annals do not record the calamitous events which followed the accession of Edward II, in 1307.

Edward, said to have been homosexual, certainly allowed himself to be dominated by a series of ill-chosen advisors. He soon found himself struggling to keep control of his kingdom, and the prohibitions on tournaments began again.

For instance, the Calendar of Patent Rolls records that Edward II, sitting at Windsor on November 20 1312, banned a tournament planned for Dunstable.

On January 1 1319, sitting at Beverley, he commissioned John de Enefeld and Simon de Friskenade to arrest all persons attempting to hold a tournament at Dunstable or elsewhere. And on January 6 1320 at York he appointed Ranulph de Charoun and William Raymundi de Clavery, king’s sergeant at arms, to arrest all persons attempting to hold a tournament at Dunstable.

But there WAS a famous tournament in Dunstable in 1309, at around Easter of that year. The date of this tournament is given in some sources as 1308 but scholars today agree on the later date, and there is evidence to suggest that it was held in late March or early April 1309.

Heraldic rolls of medieval tournaments were frequently copied in Tudor and Stuart times and there are a number of examples of the 1309 list, although the original has perished.

One copy was published by C.E. Long in his Collectanea Topographica and Genealogica in 1837. The roll and the affiliations of the knights, in what appear to be six separate retinues, have been examined in great detail by A. Tomkinson, of the Royal Holloway College, whose analysis was published in the English Historical Review in 1959.

He tried to work out how the retinues would have been divided into two equal armies of around 120 on each side. He also added the names of knights who appear in other copies of the list but were not included in Long’s published version.

There is also a short list of local knights present at the Dunstable tournament in a document at Oxford University and copied in Bedfordshire Notes and Queries (1886). It is very puzzling that these names do not appear in the detailed heraldic list.

One explanation may be that these local men, perhaps rather elderly or, alternatively, less experienced than the hardened warriors recruited by the great earls for their formidable retinues, may have been invited as a courtesy to take part in some parading or preliminary jousting prior to the main event. The heralds would not have needed to be able to identify them in the mayhem of a mêlée.

These local knights included Sir John de Pabenham, one of the most important and wealthy men in the county. Margery Bassett, in her Knights of the Shire of Bedfordshire (Bedfordshire Historical Record Society 1947), writes that Sir John had been created a Knight of the Bath at the knighting of Edward, Prince of Wales, in 1306. Sir John would have been nearly 60 in 1309.

Another local knight mentioned is Sir Ralph de Goldington, who was also elderly for the time (he died in around 1312). But Sir David de Flitwick, well into his 40s by 1309, was a doughty warrior – he had been summoned frequently for military service including four times against the Scots between 1300 and 1309. Perhaps the effect of all this warfare meant that he could not take part in the mêlée, even though he would have been an honoured guest. And another knight on that “local list” was John de Morteyn, of Tilsworth, whose extraordinary adventures will be mentioned later.

There was clearly much more going on at the Dunstable gathering than a mêlée, with the great men of the kingdom gathering together (in the absence of the king) to exchange views and plan for the future. It is significant that the very next month, at the April Parliament, these knights presented a list of grievances to their monarch.

A study of the political background to the Dunstable tournament is given in great detail by J.R. Maddicott, in his book Thomas of Lancaster 1307-1322 (Oxford University Press 1970). He uses the available evidence to argue convincingly that the event must have been held sometime between March 20 and April 7 1309.

It is quite possible to trace through many reference books the ambitious and violent careers of nearly all the men who fought in the Dunstable mêlée.

They included men who played leading parts in the turbulent years which followed, particularly the Earl of Lancaster (executed in 1322 after leading a rebellion), the Earl of Warwick (at whose castle the king’s favourite Piers Gaveston, was condemned to death), Hugh Despenser the younger (who became one of the most powerful men in the land before he was gruesomely executed), Sir Giles Argentein (the country’s most famous knight who died heroically in battle), Sir Roger d’Amory (whose bravery was noted by the king and who became a supreme and controversial influence at court), Sir Bartholomew Badlesmere (who became an unfortunate pawn in the Despenser wars and was executed), Sir Robert Holand (who led the army which sacked Loughborough in 1321) and Sir Robert Clifford (who was executed after the battle of Bannockburn).

The list of names is printed below. It’s worth giving a brief description of some of their adventures to give a further idea of the significance of their appearance at Dunstable.

The key man who was NOT there was Piers Gaveston – the king had been forced by the powerful barons to send him into exile the previous year.

Gaveston, a great tournament fighter, had become famous after his conduct and martial skills attracted the special attention of the formidable King Edward I – not a man to be easily impressed. As a result Gaveston had been assigned to be companion to Edward’s son.

But the king’s plans to provide Edward junior with a suitable role-model went sadly wrong. The young Edward became so extravagantly infatuated with Piers that the friends had to be separated. Piers was sent abroad – only to be recalled when the Prince became king.

Gaveston then became enormously influential. He was created Earl of Cornwall and married King Edward’s 13-year-old niece, Margaret de Clare, in an elaborate ceremony at Berkhamsted Castle. He controlled access to Edward, insulted the nobility with mocking nicknames and made himself enormously wealthy.

He had been appointed regent when Edward left the country to marry the French king’s daughter, Isabella. There were scandalous scenes at Edward’s coronation feast when the king openly dallied with Gaveston and ignored his queen. She was only 12 years old but her treatment was a blatant insult to her powerful relations.

Edward’s continued insistence on providing favours for Gaveston offended so many that a rebellion broke out. Gaveston was captured in 1312 and taken to Warwick Castle where he was condemned to death before an assembly of barons including the earls of Warwick, Lancaster, Hereford and Arundel.

Gaveston, still only around 29-years-old, was run through with a sword and then beheaded.

The barons then assembled in Dunstable, “filling all the country around with horses and arms”, and threatening violence to the king if their demands were not met.

Although an uneasy peace followed, the king never forgave or forgot, and the following years were marked by a constant power struggle between him and the barons. The matter was settled for a time in 1322 when the Earl of Lancaster was defeated at the Battle of Boroughbridge and executed.

The key men in this Royal victory were Hugh Despenser and his father, also named Hugh, who had eventually succeeded Gaveston as the king’s “favourites” and who became just as unpopular. The younger Despenser, who had fought at the Dunstable tournament in 1309, was married to Eleanor de Clare, eldest sister of the wealthy Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Hereford. Hereford had been killed at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 and Despenser took most of the vast de Clare inheritance for himself.

One of the many men who died at the Battle of Bannockburn, where the Scots under Robert Bruce decimated the English army, was Sir Giles de Argentein, one of the most famous and popular knights of his time and a renowned tournament fighter.

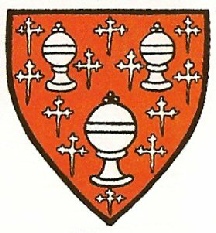

Sir Giles Argentein

Sir Giles was one of the instigators of the Dunstable tournament of 1309 and there has been a remarkable discovery among the Hertfordshire County Records of a document from Wymondley, near Hitchin, recording the cost of fodder for the horses of Sir Giles and Sir John Argentein during the Dunstable event. This seemingly unimportant invoice has been quite crucial in confirming the tournament’s date and place.

Sir Giles took a prominent part in a tournament attended by the King and Gaveston at Stepney later that year, on May 28, when he was crowned “King of the Greenwood”. (Annals Paulinius).

He was so obsessed with the excitement of tourneying that in 1302 he had deserted from the army of Edward I, hunting the rebels in Scotland, so that he could take part in a tournament in Byfleet in Surrey. The king was outraged and Giles was imprisoned. He was released to fight at the siege of Stirling Castle in April 1304 and earned a pardon. But in 1306 he again deserted from a Scottish campaign, this time to go tourneying on the continent with other young knights including Piers Gaveston. The king, again, was furious.

All was forgiven when Edward II came to power and Sir Giles accompanied Piers Gaveston on a Scottish campaign in the autumn of 1310.

The king made huge efforts to ensure that Sir Giles was part of his bodyguard at the disastrous Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. With the battle lost, King Edward (who had been in the thick of the fighting) was dragged away to prevent his capture after which Sir Giles, his honour at stake, returned to the fray. Famously, he galloped in a lone, suicidal charge to try to reach the Scottish leaders and was cut down by their battle-axes.

The defeat was a huge humiliation for King Edward, whose reign with the Despenser family became more and more unpopular. The discontent was headed by Roger Mortimer, Earl of March..

Mortimer, whose guardian had been Piers Gaveston, was imprisoned in the Tower of London in 1322 for leading a revolt against Edward in what is known as the Despenser War. He made a dramatic escape after drugging his guards and fled to France where he was joined by Edward’s long-suffering queen, Isabella. Notoriously, they became lovers, avoided assassination attempts by agents of the Despensers, and together collected an army to invade England.

Their forces paused at Dunstable on their way to London on October 1326. Edward had expected to defeat them easily, but his support evaporated and he was captured and imprisoned at Berkeley Castle.

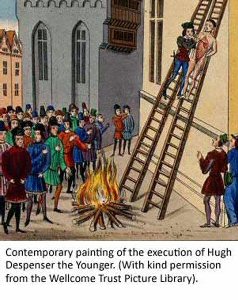

Execution of Hugh Despenser the Younger

Hugh Despenser the elder was seized at Bristol and promptly hanged, still wearing his armour. His body was hacked to pieces and fed to the local dogs, apart from his head which was displayed on a pole. Hugh Despenser the Younger was executed in Hereford in front of a huge crowd, which included Mortimer and Queen Isabella. He was stripped, dragged by a horse into the city and hung, drawn and quartered. He bore the torture with fortitude until he was near death, when he gave a great howl which produced a roar of delight from the crowd.

There’s a fascinating Dunstable sidelight to Edward’s imprisonment at Berkeley. A group of men succeeded in freeing him in the summer of 1327. But he was quickly recaptured and his rescuers fled in all directions, including two Dominican friars named John Norton and John Redmere, keeper of the king’s stud farm. (The Dominicans were huge supporters of Edward). These two were subsequently arrested in Dunstable.

The historian Kathryn Warner, who is an expert on Edward II and his reign, has discovered a letter from Thomas, Lord Berkeley, to the chancellor John Hothum on July 27 1327, telling him about the would-be rescuers and reporting that “two great leaders of this company have been arrested by the community of Dunstable and are held there in prison”.

A logical place for Norton and Redmere to seek shelter would have been the friary at Dunstable. Bearing in mind the antagonism between the canons of Dunstable Priory and their newly established rivals in the friary on the other side of the Watling Street, it was no surprise when Kathryn Warner then discovered that the Prior had a hand in their arrest.

This is revealed by a petition to Edward III from Norton and Redmere. They claimed that they had been “innocently hearing mass at the house of their order when the prior of Dunstable’s bailiffs burst in” accusing them of attempting to free Edward from Berkeley and threw them into prison. They were “at point of death” as a result.

The petition, asking that they might come before the king “to stand to right according to the law of the land”, was written probably in September or October 1327.

Another sidelight to this is an order to the Sheriff of Bedfordshire on October 18 to arrest four named men and other “malefactors” who were lying in wait day and night for the prior of Dunstable and his men. Was this a rescue attempt? One of the named men was Philip de Wiubbesnade (Whipsnade).

Edward’s son, Edward III, was still a youth when his father was deposed, and Roger Mortimer became, in effect, ruler of England. Mortimer is said to have arranged for Edward II to be murdered at Berkleley Castle.

Once again, there are Dunstable sidelights to the troubled years that followed. Earl Henry of Lancaster led a brief rebellion and he and many others assembled at Bedford early in 1329. Mortimer and Queen Isabella (in full armour) rode out to meet them in battle, before efforts by senior clergy to arrange a truce were successful.

After it was all over an inquisition was held in Dunstable in February 1329 which concluded that “no person of the town of Dunstaple bore arms against the king…the jury are quite ignorant of the names of persons so armed now at Bedford, because they of the town of Dunstaple have no knowledge without the liberty of the said town…”

However, into the Dunstable picture now appears a local knight, Sir John de Morteyn of Marston Moretain and Tilsworth, who had been included in that “local list” of men present at the 1309 Dunstable tournament.

Sir John had been a supporter of the Despenser faction and had been of such importance that he and the men of his household riding with him had been allowed by a Royal order in March 1326 to bear arms “that he may not suffer by attack of evil doers who threaten him in many ways”. (Cal Patent Roll 1324-7 p 254). After the fall of the Despensers, he had obtained a pardon but following the confrontation at Bedford he found himself accused by the Prior of Dunstable of taking part in the Earl of Lancaster’s rebellion.

The Prior claimed that Sir John was associated with Thomas Wake (part of the Lancaster faction) and other rebels.

Sir John vigorously defended himself to such convincing effect that in 1330 Prior John himself was committed to prison at the local assizes for conspiracy against Sir John.The Prior was liberated on finding sureties.

The report of the proceedings was discovered by Toddington historian Joseph Hight Blundell who mentions it in his 1912 book The Blundells of Beds and Northants and quotes Assize Rolls Beds No 26, 4 Edward III, m 50 d.

The Prior of Dunstable who found himself so disastrously embroiled in the nation’s lethal politics was John of Cheddington who had been appointed in 1302. Somehow he survived all the turmoil and remained as Prior until his death in 1341.

Kathryn Warner, in the English Historical Review (August 2011), has written about an alleged conspiracy by the Earl of Kent who was beheaded for treason in 1330. Among the co-conspirators arrested was a man called Will de Donestaple.

Ms Warner’s discoveries include a mention in a 1323 chancery roll of a page in King Edward II’s chamber named “Wille de Donestaple” who might well have been the same man. Will of Dunstable, now a clerk, is identified again on October 9 1325 when the king bought 47 caged goldfinches as a present for his niece, Eleanor Despenser, and Will was paid to look after them until Eleanor took possession.

The Earl of Kent’s execution started a chain of events which led to Mortimer’s downfall. Edward III asserted his independence and organised a coup. Mortimer was taken by surprise after Edward’s men entered Nottingham Castle through a secret passage. He was executed in November 1330 at Tyburn where his body was left hanging for two days and nights. Queen Isabella, by then known by her enemies as “the She Wolf of France”, was confined to Berkhamsted Castle.

Edward III established order in his kingdom and, secure on his throne, began to actively encourage tournaments. He attended a number in Dunstable including one which is dated in the Victorian County History as 1329 (Pipe Roll 11 Edw III 36d).

This would have been before Edward’s “independence” so it would have been authorised by Roger Mortimer, despite the danger, or perhaps because the “inquisition” that year had assured him of Dunstable’s loyalty. In fact, an account of the money spent in Dunstable for the stay of the royal household during the tournament over six days in October includes the name of the Earl of March – Roger Mortimer.

There is, incidentally, a record of Mortimer holding a “Round Table” at Bedford in 1328 (Knighton, Chron, Rolls Ser, i.449) which was an increasingly popular type of tournament involving mock-Arthurian pageantry and jousting rather than the old-style mêlée. Perhaps the 1329 Dunstable tournament was similar and it was certainly an elaborate occasion – King Edward was provided for the occasion with a suit of armour covered in white muslin and red velvet (Edward III and the Triumph of England, by Richard Barber, 2013).

The 1329 Roll records that “£4 15s 5d was spent in the repair of houses as follows: 1,000 tiles, 1,000 laths, 4,000 lath nails, 500 spykyngnails, 24 boards for planking, lime, sand and white clay and carriage of same bought for repair of divers houses and other outhouses for the stay of the king and his faithful servants in his company, within the court of the late John Durrant at Dunstable for the tournament there in the 3rd year: -29s 4d.

“Also in wages of 7 carpenters, 2 tiles and their 4 assistants, each tiler at 6d and each assistant at 3d a day, 2 men for plastering the walls and other defects in divers places within the court for 8 days at 4d a day, together with 6s 6d paid to 2 men for mending the gutter with lead and other defects of the rooms there. By a stipulated contract wages were 66s 1d.”

The roll is a summary of a more-detailed account by Augustine le Waleys, translated here by Charles Kightly, for various costs and expenses made at Dunstable for the stay of the Lord King and the Lady Queen, their households, and the Earl of March at the tournament.

This document gives the date of the royal visit (October 7 or 8 until October 12) and even includes the names of some of the men who were paid for their work at Dunstable: carpenter John Pygoyn and his six mates; master tilers John ??? and William le Freynss; mason William de Hokham; and plumber William de Gatesdene. Their work continued from September 17 until October 4.

These are rare records of the kind of preparations deemed necessary. But there would have been much more. A wooden stand, gaily decorated, would have been erected for the more-important spectators. And earthworks marked by stakes and fences would have been built to contain the men and horses taken hostage, and to accommodate squires and the sp are supply of weapons. This area was known as the lists.

are supply of weapons. This area was known as the lists.

Coronation of Edward III of England 1327 - 1377

During Edward III’s reign, the style of tournaments changed, with jousting between two knights beginning to attract more attention than the great mock battles between opposing armies.

These individual trials of strength and skill had originally been a mere prelude to the main battle, with knights demonstrating their martial skills on the night before the mêlée or in the foreground of the battlefield while the armies manoeuvred behind them.

Initially, these jousts were a chance for the younger knights to gain experience before the really serious business began. But everyone, spectators and warriors alike, became more and more fascinated by the feats of arms demonstrated by their champions. Tournaments developed into more formal affairs, with combatants galloping with lowered lances alongside a tilting barrier in a much more confined space, surrounded by stands. They were grand social occasions, with parades, pageantry and sumptuous outfits for both men and women.

Despite the rules and formality, they remained dangerous affairs. For instance, John Hastings, Earl of Pembroke, was killed while jousting in 1389 and John, Lord Beaumont, was killed jousting in 1342.

The tilting barrier, originally a long stretch of cloth and later a stronger barrier of wood, was introduced at some point in the 14th century. It prevented the horses from colliding and enabled the knights to concentrate on aiming their lances. Dedicated areas for tilting started to be built in the time of King Henry VIII and, confusingly, jousting became the recognised term for this kind of combat between two knights. Previously, jousting (meaning “a meeting”) referred to combat on an open field.

Edward III deliberately encouraged the notion that knights were glamorous, chivalrous figures. He had founded the Order of the Knights of the Garter at Windsor and fostered comparisons with the legendary King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. It made more desirable the award of a knighthood, which was given automatically to men of a certain wealth who were then required to buy armour and become officers in the king’s army.

Previously, a knighthood had not necessarily been a welcome honour. The Court Rolls of Edward III record that on February 28 1334, the king granted a pardon to Thomas le Brut, “who lately received from the king at Dunstaple the order of knighthood, for not having taken the same before Trinity last pursuant to the king’s proclamation.”

Similarly, in 1335, the king pardoned Peter Eskudemore for not having taken the order of knighthood pursuant to the proclamation made in the county of Wilts, “he having taken the same in Dunstaple…”.

These men may simply have wanted to avoid leaving their families in Dunstable to take part in the ongoing battles against the Scots. These wars came to a temporary conclusion in 1333 when King Edward III was victorious at the battle of Halidon Hill and forced King David II of Scotland (son of Robert Bruce) to seek refuge in France.

Edward returned in triumph from the campaign and met the nobles from London and the south for a celebratory tournament at Dunstable, probably between January 20 and 23, 1334.

A list of knights who took part in that Dunstable tournament is another rare relic of those times. It was transcribed by C.E. Long from rolls which also included the detailed descriptions of the knights’ arms.

The list includes, interestingly, Hugh Despenser, the son and grandson of the men who had been executed so horribly, and who was re-establishing the family name. There’s also a mysterious “Sir Lionel” who was almost certainly the king himself, fighting incognito.

Another very special name on the 1334 list is Robert Benhale, a famous tournament fighter who had particularly distinguished himself at Halidon Hill. His exploit is described in Juliet Barker’s book The Tournament in England 1100-1400. Benhale took up a challenge to fight in single combat a giant Scottish warrior as a prelude to the main battle. Benhale attacked him on foot, armed with only a sword and shield, and was victorious.

Richard Barber, in his forthcoming book Edward III and the Triumph of England, has analysed in detail the list of knights at the 1334 tournament and shows that 89 of them were either members of the king’s household or fought in 1346 at the battle of Crecy (or both). It shows that the hard core of tourneyers were very similar to the core group of Edward’s armies. He adds that 36 of the contestants had labels on their arms, a heraldic device indicating that in 1334 they had not yet inherited their estates.

Dr Barber, who has found a record of a payment of £160 to the keepers of the king’s studs for buying horses for the tournament, also discusses the identity of “Sir Lionel”, which hinges on Edward’s nickname rather than any reference to the Lionel of Arthurian legend, who was a disobedient figure and hardly a role-model for a king.

Edward had been called the “little lion” by Mortimer and Isabella, and at a tournament at Wigmore on September 6 1329 he was given a golden goblet with “four escutcheons bearing the arms of leonell”. In that year he had been provided with a suit of armour covered in white muslin and red velvet – the same colours as detailed in the blazon for Sir Lionel’s shield in Dunstable 1334, in which year Peter de Bruges was paid for “four entire suits of armour in the arms of Lionel for jousts and tournaments”.

Another clue given by Dr Barber to the identity of Sir Lionel is that his shield as described at Dunstable is, in fact, the arms of the earl of Chester. That was Edward’s title before he came to the throne and although in 1334 the arms technically belonged to his three-year-old son, Edward, the Black Prince, (who was created earl of Chester in March 1333) the king must have retained the badge for the Dunstable event. Who else would have dared?

In 1342, almost immediately after yet another war against the Scots (King David had returned), Edward III announced a tournament to be held at Dunstable in honour of the betrothal of Lionel of Antwerp, the king’s son (still only a child), to Elizabeth de Burgh, daughter of the murdered Earl of Ulster.

It was attended by the royal family and most of the nobility and was a particularly spectacular affair, with so much pageantry, parading and preliminary jousting that the main event, the great mêlée, did not begin until the sun was going down. To the disappointment of many, there was little time for ransoms to be won or lost, and this is generally believed to have been the last mêlée-tournament to be held in England.

A particularly bloody tournament held later the same year, at Northampton, was described as “hastiludes”, a term covering a variety of martial games.

Holinshed records the earlier tournament saying: “There was a great juste kept by King Edward at the towne of Dunstable, with other counterfeited feats of warre, at the request of diverse young lords and gentlemen, wherat both the king and queene were present with the more part of the lords and ladies of the land”.

There is also a record of this 1342 tournament in Adam Murimuth’s, Continuatio Chronicarum, kept between 1303 and 1347. This translation from the Latin is by Steven Muhlberger

“And immediately a tournament was announced at Dunstaple, on the Monday before the upcoming Quadragesima Sunday. And the King of England returned around the Feast of the Conversion of St. Paul, (ie January 25) in the sixteenth year of his reign. To this tournament came just about all the young men at arms of England, but no foreigners.

“In this tournament the king took part like a simple knight; and all the young earls of the realm were there, namely the earls of Derby, Warwick, Northampton, Pembroke, Oxford, and Suffolk. But the earls of Gloucester, Arundel, Devon, Warrene, and Huntingdon were absent, whom age and infirmity excused. But the barons of the north and of other parts of the realm were there, so that the number of helmeted knights reached 250 or more.

“But they were so late going out in the field that nightfall prevented the affair from proceeding, so that scarcely ten horses were lost or gained. After that the king, earls and barons went to London, to discuss what out to be done in the summer.

“Likewise, fifty days after Easter, the king held hastiludes at Northampton, where many nobles were seriously wounded and some mutilated, and many horses were lost, and Lord John of Belmont was killed.”

Some idea of the splendour of the Dunstable occasion can be gained from the researches of Stella Mary Newton, whose book “Fashion in the Age of the Black Prince,” gives details from inventories kept in the workshops in the Tower of London of the clothes made specially for the appearances by the king, queen and princesses at Dunstable.

The king and his knights wore suits of green cloth with hoods and a white border on which were embroidered Catherine wheels, with letters in jewels and pearls spelling the motto “It is as it is”. The king’s suit was lined with silk and involved some goldsmith’s work in its fastenings.

Catherine wheels with the same motto formed the centrepiece of the coverlet for the king’s bed, made for the same event, its corners filled with the arms of England and France enclosed in circles. The arms of Lionel of Antwerp were also included in the design.

The queen’s ghita (perhaps a medieval term for a robe) was made of scarlet cloth, a gift of the king, powdered with a design made up of squares of enamel, worked with gold thread and, in the middle of each enamel square, a quatrefoil of pearls with a ring in its centre. Fifteen ounces of gold and silver in the form of plate and thread were used on this work.. Embroiderers and a furrier worked for days on the garment.

The ghitas for the two princesses were made of black cloth, also a gift from the king. They were also powdered with enamel squares and embroidered in gold.

The bailiff’s accounts for the Manor of Grovebury at Leighton Buzzard throw a further light on the tournament. They record money spent by Lady Maud, tenant of the Manor from 1338, for her lodgings and breakfast at Dunstable and on providing a gift (four quarters of wheat “for the tournament”) to her brother, the Earl of Derby.

This is fascinating because Lady Maud’s daughter was the rich heiress Elizabeth de Burgh, whose betrothal to the king’s son was being celebrated at the tournament. Perhaps the king was being particularly courteous in arranging the event at Dunstable, so close to Lady Maud’s home.

Maud was the daughter of the blind Earl of Lancaster, grandson of Henry III. She was the widow of William de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, who was assassinated in 1333. Her brother, a renowned soldier, became Earl of Lancaster on the death of his father in 1345.

THE COMPLETE LIST FOR THE 1309 TOURNAMENT

Below is the list of knights at the 1309 tournament in Dunstable with heraldic descriptions of their arms as recorded by the heralds at the time. It was copied and published by C.E. Long in 1837 and is printed here with the original spellingsof their names.

They are listed in the original order, which provides some indication of the retinues of their leaders, who were the earls of Gloucester, Hereford, Warwick, Lancaster, Surrey and Arundel. Knights unattached to retinues were printed under the heading “de la Comune”. Or = gold, Argent = silver, Azure = blue, Gules = red, Sable = black, Vert = green, Purpure = purple.

In brackets after the copy of each original entry is a version with alternative spellings and other details, compiled in part with the help of Joseph Foster’s book, Feudal Coats of Arms and Pedigrees.

A project to provide illustrations of all the Dunstable arms is being undertaken by Brian Timms who already has a large website of medieval heraldry. The Dunstable lists will join others on www.briantimms.fr

LE COUNTE DE GLOUCESTRE,

Or, 3 chevronels Gu (Earl of Gloucester, Gilbert de Clare)

Sr Robert Darcy, Ar 3 cinquefoils Gu a border indented Sa

Sr Nichol de Wyfryngdon, Gu a lion ramp Ar crowned Or (Sir Nichol de Wokingdon?)

Sr Roger Tyrell, Az a lion ramp Ar langued Gu a border indented Or (Sir Roger Tyrrell of Herefordshire)

Sr Henry Penbryg, Barry of 6 Or and Az a bend Gu (of Herefordshire?)

Sr Laurence de Hameldene, Ar fretty Gu the fret charged with fleurs de lys Or (of Suffolk)

Sr Gilles d’Argentein, Gu semee of cross crosslets, 3 Covered cups Ar (Sir Giles Argentine of Cambridge, killed at Bannockburn)

Giles Argentein

The exploits of Sir Giles Argentein are world-famous. This elaborate depiction of Sir Giles in tournament action is one of a series of miniature metal models on sale in the USA. It was designed by Thor Johnson and crafted in Russia. The image here is used by permission of the AeroArt St Petersburg Collection, 11797 Hollyview Drive, Great Falls, VA 22066-1333, www.aeroartinc.com tel 703-406-4376

Sr Gilibert de Leffend, Barry nebuly of 6 Sa and Ar a label of 3 pts Gu (Sir Gilbert Delefend)

Sr Nichol Poynz, Barry of 8 Or and Gu (Sir Nicol Poynz, banneret of Cory Malet)

Sr John de Bellyns, Ar 3 lioncels ramp Gu (Sir John Belhous of Essex)

Sr Roger d’Amori, Barry nebuly of 6 Ar and Gu a bend Az (Sir Roger Amory, baron 1317. He caught the king’s eye by his bravery at the battle of Bannockburn and became a supreme influence at court. Died from wounds after the battle of Boroughbridge)

Sr Thomas Lovel, Barry nebuly of 6 Or and Gu a bendlet Or (Sir Thomas Lovell of Oxfordshire)

Sr Richard de Clare, Or, 3 chevronels Gu a label of 3 points Az

Sr John de Quingeton, Ar on a chief Az 2 fleurs de lys Or (Sir John de Evington or Ovington)

Sr Oliver de Saynt Amand, Or fretty Sa ona chief of the 2nd two mullets Ar pierced Vert (Sir Oliver de St Amand of Gloucestershire)

Sr Nichol de Clare, Or, 3 chevronels Gu a border indented Sa (Sir Nicholas de Clare of Gloucestershire)

Sr John Leffend, porte Ar, 2 barres unde de Sa (Sir John de le Fend)

Sr Will’m Flemyng, Gu fretty Ar a fess Az (Sir William Flemyng of Gloucestershire)

Sr John de Saynt Oweyn, Gu a cross Ar, the 1st quarter charged with a shield of Clare (Sir John de St Owen of Herefordshire)

Sr Robert Boutevilain, Ar 3 crescents Gu (killed at battle of Bannockburn)

Sr Fouke Payfote, Ar 5 fleurs de lys Sa 3, 1, and 1, a label of 3 pts Gu

Sr Geoffrey de Sey, Quarterly Or and Gu (Sir Geoffrey de Say, banneret, baron 1313)

LE COUNTE DE HEREFORDE, Az a bend Ar cotised Or betw 6 lioncels ramp, Or (Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford, Constable of England, captured at battle of Bannockburn 1314, killed by a pikeman at Boroughbridge 1322).

Sr Theibault de Verdon, Or, fretty Gu (Sir Theobold de Verdon)

Sr Waulter de Beauchampe, Gu a fess betw, 6 martlets Or (Sir Walter de Beauchamp)

Sr John Bodyngrelys, Ar a fess and in canton a mullet Gu (Sir John Dodingsell/Odingsells, banneret)

Sr Th de Ferrars, Vaire Or and Gu a quarter charged with the coat of Bohun (Sir Thomas de Ferrers)

Sr Roger Candos, Or, a lion ramp double-queud Gu

Sr Bartholomew de Enefende, Ar on a canton Sa a mullet Or (of Middlesex)

Sir Will’m de Vaulx, Or, a shield within an orle of 8 martlets Gu (Sir William de Vaux)

Sr John de Ferers, Vaire Or and Gu (Sir John de Ferrers)

Sr John de Arcourt, Gu 2 bars Or (Sir John de Harcourt, banneret, of Leicestershire)

Sr Walter Bastervile, Ar on a chevron Gu betw 3 mullets Orn (Sir Walter Baskerville)

Sr Piers de Breysy, Or, a lion ramp Az langued Gu (Braose of Gloucestershire?)

Sr Richard Louvell, Or, semee of cross-crosslets and a lion rampant Az langued Gu (Sir Richard Lovell, banneret)

Sr John de Weston, Ar a fess Sa within a border indented Gu Bezantee

LE COUNTE DE WARWIKE, Gu a fess betw 6 corss-crosslets Or (Guy Beauchamp, 2nd Earl of Warwick)

Sr Henry Fitz Hugh, Az fretty Or, a chief Or, a label of 3 pts Gu (son of Sir Henry le Fitz Hugh, banneret)

Sr Gilbert Talbot, Gu a lion ramp within a border indented Or (of Gloucestershire)

Sr Will’m la Souche, Gu 10 Bez a label of 3 pts, Az (Sir William la Zouche, banneret, of Haringworth, baron 1308)

Sr John Beauchamp du Conte de Warwike, Gu a fess between 11 billets Or, in chief 7 & 4 in base

Sr Godfrey de Meus, Az 6 griffons sergeant Or, 3,2, & 1 (Sir Godfreyt de Meux)

Sr John Hamelyn, Gu a lion ramp Ermine, crowned Or (Sir John Hamlyn of Leicestershire, bore arms at battle of Boroughbridge,1322)

Sr Will’m le Blond, Barry nebuly of 6 Or and Sa (Sir William le Blount, of Warwickshire)

Sr Th. le Blond, Gu a fess betw 6 martlets Ar (Sir Thomas Blount of Warwickshire)

Sr Andrew de Herteley, Ar a cross Gu in canton a mullet Sa (Sir Andrew Harcla / Hartecley of Cumberland, baron 1321, Earl of Carlisle 1322)

Sr Robert de Clyfforde, Checky Or and Az a fess Gu (Sir Robert de Clifford, baron 1299, executed after Bannockburn)

Sr John de Castre, Az an eagle disp barry of 10 Ar and Gu (of Norfolk?)

Sr Edmon Bacon, Gu on a chief Ar 2 mullets Sa pierced Or (Sir Edmond Bacon)

Sr Thomas de Shefelde, Gu a fess betw 3 garbs Or (Sir Thomas de Sheffield)

Sr Will’m Bayons, Gu 2 bars and in chief 3 escallops Ar (Sir William Bayous of Lincolnshire)

Sr Will’m Rydell, Gu a lion ramp within a border ind Ar (Sir William Riddell “of the north”, battle of Boroughbridge 1322)

Sr Nichol de Hastings, Or a maunch Gu a label of 3 points Az (Sir Nichol de Hastang of Staffordshire)

Sr Will’m de Rye, Gu a bend Ermine, a label of 3 pts Or

Sr Will’m Latymer, Gu a cross flory Or (Sir William Latimer of Corby)

Sr Henry Tyes, Ar a chevron Gu (banneret, of Chilton, bore arms at siege of Calais, executed after the battle of Boroughbridge)

Sr Waryn de Lylle, Gu a lion pass gard Ar crowned Or (Sir Warin de Lisle of Rutland)

Sr Robert d’Offord, Sa a crosss engrailed Or (Sir Robert de Ufford, baron 1309)

Sr Gilbert de Heyeton, Gu a cross flory Or (Sir Gilbert de Heton)

Sr Thomas Latymer de Boursary, Gu a cross flory Or, a label of 3 pts Sa each pt charged with a Plate (Sir Thomas de Latimer, le Boursary or Bouchari)

Sr Hughe le Despenser, Party per cross Ar and Gu a bend Sa the 2d and 3d quarters fretty Or, and over all a label of 3 points Az (Sir Hugh Despenser the younger)

Sr Roland de Lokyn, Bendy of 6 Gu and Ermine (Sir Renard or Roland de Cokyn/Luckyn/Cokyn/Qukin)

Sr Alexander Cheveril, Ar 3 lioncels rampant Sable, langued Or (Sir Alexander Cheverell of Wiltshire)

Sr Raot de Hethman, Az fretty Ar a border inden Or (Sir Raol or Roos de Hethman)

Sr John de Hanlowe, Ar a lion ramp Az langued Gu gutte d’Or (of Oxfordshire)

Sr Richard de Hammore, Barry nebuly of 6 Gu & Ar

Sr Robert de Cendale, Ar a bend Az a label of 3 points Gu (Sir Robert de Kendale of Hertfordshire)

Sr Will’m Montagu, Ar 3 lozenges in fess Gu (baron 1317-18)

Sr Robert Hastang, Az a chief Gu a lion ramp Or (Sir Robert de Hastang of Staffordshire)

Sr Rauf de Gorges, Lozengy Or and Az (Sir Raffe de Gorges, bore arms at the siege of Carlaverock 1300)

Sr Ancel le Mareshal, Gu a bend engrailed Or, a label of 3 pts Ar (Sir Ancel Marshall)

Sr John Cone, Gu a bend Ar cotised Or (Sir John Cove/Coue/Cowe of Norfolk)

Sr Will’m le Mareshal, Gu a bend engrailed Or (Sir William Marshall, banneret, baron 1309, bore arms at the siege of Carlaverock 1300)

Sr Bartholomew de Badlesmere, Ar a fess double-cotised Gu (bore arms at the battle of Boroughbridge and was executed)

Sr Roger Bynleyn, Ar an eagle disp Vert (Sir Roger de Bilney of Norfolk)

Sr Richard Foliet, Gu a bend Ar (Sir Richard Foliott of Norfolk)

Sr John Bracebrige, Vaire Sa and Ar a fess Gu (Sir John de Bracebridge of Lincolnshire)

Sr Henry Leybourne, Az 6 lioncels ramp Ar a label of 3 pts Gu (Sir Henry de Leyburn)

Sr Esteven Durwas, Gu a lion ramp double-queued Or (Sir Stephen Burghersh?– Sir Bartholomew Burghersh of Kent was the King’s Chamberlain)

Sr John de Haustede, Ar on a bend Vert 3 eaglets dis Or Sir John de Hausted)

Sr Morys le Broun, Az a cross moline Or (Sir Morys le Brune, a baron 1315)

Sr John de Haule, Gu 3 crescents Or

Sir Robert de Haustede, Gu a chief checky Or and Az over all a bend Ar (Sir Robert de Hausted)

Sr John de Knoville, Ar 3 mullets Gu a label of 3 pts Az

Sr John de Somary, Or, 3 lions pass Az langued Gu (Sir John Somery)

Sr Rauf Basset, Or, 3 piles conjoined in base Gu a canton Erm (banneret)

Sr Henry de Appilby, Az 6 martlets Or, 3, 2, & 1 (Sir Henry de Appelby of Staffordshire)

Sr Robert de Rocheford, Quarterly Or and Gu a border indent Sa (Sir Robert de Rochford)

Sr John de Graundone, Vaire Sa and Ar a bend Or (Sir John Grendon of Warwickshire)

Sr Will’m Beauchampe, Gu a fess betw 6 martlets, within a border indent Or (Sir William Beauchamp)

Sr John de Ways, Gu a shield Or charged with 2 lions pass Az within an orle of 8 martlets Or (John Wayz/Wasse)

LE COUNTE DE LANCASTRE, Gu 3 lions pass gard Or, a label of 3 points Az each point charged with as many fleur-de-lys of the 2nd (Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, great enemy of the king, executed after battle of Boroughbridge)

Sr Robert Fitz-Nel, Barry paly of 6 Ar and Gu (Sir Robert Fitz Nele)

Sr Philippe de Baringtone, Ar a lion ramp double-queued Sa langued Gu charged on the shoulder with a fleur de lys Or (Sir Philip de Baringtone of Leicestershire)

Sr Robert de Stapeldoune, Az a lion ramp double-queued Or, langued Gu (Sir Robert de Stapleton of Staffordshire)

Sr Robert de Holand, Az semee of fleurs de lys, a lion ramp gard Ar (banneret, a baron 1314)

Sr John de Arderne, Gu 10 cross-crosslets 4,3,2, and 1, and a chief Or (of Salop, crusader)

Sr Robert Wateville, Ar 3 chevronels Gu a border indented Sa (Sir Robert Wateville of Essex, baron 1326)

Sr John Twyford, Ar 2 bars Sa a canton of the 2d charged with a cinquefoil Or (of Leicestershire, bore arms at the battle of Boroughbridge)

Sr Roger de Wateville, Ar 3 chevronels Gu in canton a martlet Sa (Sir Roger de Wateville of Essex)

Sr Adam Banastre, Ar a cross flory Sa (of Lancashire)

Sr Robert Pulford, Sa a cross flory Ar (Sir Robert Pulsford of Lancashire)

Sr Will’m de Sule, Gu 2 bends Or, a label of 3 pts Ar each point charged with 4 barrulets Az (Sir William de Suley)

Sr John Darcy, Ar a shield Sa betw 3 cinquefoils Gu (Lord of Dunston and Stallinborough, Lincolnshire, friend of Piers Gaveston)

Sr Hugh Meinel, Vaire Ar and Sa a label 3 pts Gu (Sir Hugh Menell/Menyle/Menyll/Meynell of Cambridgeshire)

Sr Roger Somerton, Ar a cross flory Sa (Sir Roger de Swinnerton, baron 1337)

Sr Michel de Laverington, Sa fretty Ar a label of 3 points Or

Sr Willm de Kyme, Gu a chevron between 10 cross-crosslets Or a label of 3 pts Ar (Sir William de Kyme, also bore arms at the battle of Boroughbridge 1322)

Sr Richard de Peria, Quarterly Ar and Sa in the 1st quart a mullet Gu pierced Or (Sir Richard de Perers, battle of Boroughbridge)

Sr Urian de Saint Pere, Ar a bend Sa a label of 3pts Gu (Sir Uryan de St Pierre, banneret)

Sr Edmon Talbot, Ar 3 lioncels ramp Gu (Sir Edmond Talbot of Lancashire)

Sr Thomas de Vere, Quarterly Gu and Or in the 1st quarter a mulletAr a label of 3 pts Az

Sr Robert Pirpont, Ar a lion ramp Sa langued Gu debruised by a bendlet Or ((Sir Robert Pierpont)

Sr Henry Lekeburn, Ar a fess dancette betw 8 cross-crosslets Sa (Sir Henry de Lekebourne)

Sr John de Laleche, Ar on a bend Gu 3 stag’s heads erased Or (Sir John de la Vache/de la Beche, of Berkshire)

Sr Philippe de Hastinges, Or, a fess and in chief 2 mullets Gu a label of 3 pts Az (Sir Philip de Hastings of Oxfordshire)

Sr Nichol de Segrave, Sa a lion ramp Ar langued a label of 3 pts Gules (Sir Nicholas de Segrave, baron 1295-1322, battle of Boroughbridge)

Sr Thur Bardolf, Az 3 cinquefoils Or (Sir Thomas Bardolf)

Sr John de Weyland, Az a lion ramp Ar langued Gu debruised by a bendlet Gu

Sr Geoffrey Wauteville, Sa semee of cross-crosslets, a lion ramp Ar langued Gu (Sir Geoffrey Wateville)

Sr John de Fyliol, Vaire Ar and Az on a canton Gu a mullet Or (of Essex)

Sr Gerard de Lille, Gu a lion pass gard Ar cro Or (Sir Gerard de Lisle of Rutland)

Sr John de Argentein, Gu 3 covered cups Ar (Sir John Argentine, of Wymondley, Hertfordshire, knight banneret, 2nd baron)

Sr Robert de la Crey, Ar a shield Gu debruised by a bendlet Sa

Sr Estienne de Segrave, Sa`a lion ramp Ar langued Gu crowned Or, and charged on the shoulder with a fleur-de-lys of the 3rd (Sir Stephen Segrave)

Sr Henry de Segrave, Sa a lion ramp Ar langued Gu crowned Or, debruised by a bendlet engrailed of the 3rd (of Leicestershire)

LE COUNTE DE WAREYNS, Checky Or and Az (John de Warenne, earl of Surrey and Sussex, grandson of John de Warenne, earl of Surrey, whose only son, William, was killed at a tournament in Croydon, December 15 1285)

Sr Will’m Paynell, Barry of 10 Ar and Sa an orle of 8 martlets Gu

Sr Constantine de Mortimer, Or, 6 fleurs de lys Sa 3, 2, and 1 (Sir Constantine Mortimer, son of William Mortimer, baron, of Attleborough)

Sr John de Moubray, Gu a lion ramp Ar (Sir John Mowbray, banneret)

Sr Robert de Strangure, Az semee of billets a cross Ar (Sir Robert Stangrave/Stongrave, fought at battle of Boroughbridge)

Sr Adam de Hodelestone, Gu fretty Ar a label of 3 points Az (Sir Adam Hudleston)

Sr Nicholl Gentill, Or, on a chief Sa 2 mullets Ar pierced Gu (of Sussex or Surrey)

Sr John de Gray, Barry of 6 Ar and Az in chief 3 Torteaux (Sir John de Grey)

Sr Michel Poinges, Barry of 6 Or and Vert, a bend Gu (Sir Michael Poynings of Surrey)

Sr Thomas Poninges son Frere, Same, the bend charged with 3 mullets Ar (Sir Thomas Poynings, Michael’s brother)

Sr John de Wisham, Sa`a fess betw 6 martlets Or (of Gloucestershire)

Sr Richard Hachit, Ar on a bend Gu cotised Sa 3 fleurs de lys Or (Sir Richard Hacklute)

Sr Michel Malewerers (Nicholas Maleymeyns?) Ar a bend engrailed Gu (Sir Michael Maleverer)

Sr Willm Wasteneis, Sa a lion ramp Ar langued and collared Gu (Sir William de Wasteneys of Staffordshire)

Sr Payn Tipetoft, Ar a saltire engrailed Gu (Sir Payn de Tibetot, banneret, baron 1308)

Sr Baudewyn de Maners, Ar a saltire engr Sa (Sir Bawdwyn de Manners of Cambridgeshire)

Sr Robert de Shurland, Az 6 lioncels ramp Ar langued Gu a canton Ermine (Sir Robert Shirland of Kent, at siege of Carlancross 1300)

Sr Walter Beryngham, Ar on a bend Gu cotised Sa 2 escallops Or (Sir Walter Bermingham)

Sr John Blocte, Or, an eagle double-headed disp Gu (Sir John Bluet of Hants)

Sr Thomas de Coudrey, Gu 10 billets Or (Sir Thomas de Coudray of Berkshire)

Sr Henry de Glastingbury, Ar a bend engr Sa (Sir Henry de Glastonbury of Somerset)

Sr Richard Basset, Barry paly of 6 Or and Gu a border Sa Bezantee

Sr George de Thorpe, Checky Or and Gu on a fess Ar 3 martlets Sa (of Norfolk)

Sr Simon de Cotsende, Ar a saltire engr Sa a label of 3 pts Gu (Sir Simon de Cokefeld/Cocfeld of Suffolk)

LE COUNTE DE ARONDELL, Gu a lion ramp Or (Edmund Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel, beheaded at Hereford 1326 on order of Roger Mortimer)

Sr Willm Bagot, Ermine, on a bend Gu 3 eaglets dis Or (Sir William Bagot of Cambridgeshire)

Sr John Descures, Az fretty Or (Sir John de Scures of Wiltshire)

Sr Roger de Sein John, Ermine, on a chief Gu 2 mullets Or, pierced Vert (Sir Roger de St John of Wiltshire)

Sr John de Silton, Or, on an eagle disp Vert, a bendlet compony Ar and Gu

Sr Hugh Croft, Quarterly per fess indented Az and Ar in the 1st quarter a lion pass gardant Or (of Salop)

Sr John Pesche, Gu a fess betw 8 cross-crosslets Ar (Sir John Pecche, of Warwickshire, banneret at battle of Boroughbridge 1322)

Sr John Jos, Ar an eagle disp Sa a bendlet compony Or and Gu (Sir John Joce)

Sr Fouke le Strange, Ar 2 lions pass Gu (banneret, baron 1309)

Sr John le Strange, Gu 2 lions pass Ar within an orle of 8 martlets Or (Sir John L’Estrange)

Sr Fouke Fitzwaryn, Quart per fess indent Ar and Gu in the 1st quarter a mullet Sa (Sir Fouke Fitwaryn)

Sr Thoms Corbet, Or 3 crows Sa

Sr Will’m Fitzwill’m, Lozengy Ar and Gu (Sir William Fitz William

Sr Will’m Waincourt, Ar a fess indented betw 8 billets Sa (Sir William Deyncourt)

(de la Comune)

Sr Robert Tony, Ar a maunch Gu (Sir Robert de Toni of Castle Matill, banneret, a baron 1299, battle of Falkirk 1298, siege of Carlaverock 1300)

Sr Henry de Den, Ar a fess dancette betw 3 crescents Gu (Sir Henry Deane of Northamptonshire)

Sr Gilbert Pesche, Ar a fess betw 2 chevrons Gu (Sir Gilbert Peche of Corby, banneret, baron 1299, battle of Falkirk 1298)

Sr Walter Haket, Ar 2 bends Gu (Sir Walter Hacket of Derbyshire)

Sr Will’m de Kroy, Gu a cross engr Or, debruised by a bendlet Az (Sir William de Crey of Kent)

Sr Richard Capille, Ar a chevron Gu betw 3 Torteaux (Sir Richard de Capelle of Herefordshire)

Sr Roger de Mortymer le Filz, Barry of six Or and Az on a chief of the 1st two pallets betw as many gyrons of the 2d, based dexter and sinister; an inescocheon Ar charged with a lion ramp Purpure (Probably Roger Mortimer, the only legitimate son of Sir Roger Mortimer of Chirk).

Sr Thomas de Ufforde, Sa a cross engr Or, surmounted by a bendlet Ar (Sir Thomas de Ufford)

Sr Hamon le Strange, Gu 2 lions pass Ar surmounted by a bendlet Or

Sr John de Willington, Gu a saltire vaire Ar and Az (banneret, baron 1329)

Sr Thomas de Gorneye, Barry paly of 6 Or and Gu (Sir Thomas de Gurney of Somerset)

Sr Will’m Wanton, Ar on a chevron Sa 3 eaglets disp Or (of Gloucestershire)

Sr John le Warre, Gu crusilly and a lion ramp Ar a label of 3 pts Azure (John de la Warr, son of Roger de la Warr, baron, of Isfield)

Sr Thomas Berkeley, Gu on a chevron betw 10 roses Ar (battle of Falkirk, 1298)

Sr John de Waleys, Ermine, a bend Gu (of Somerset)

Sr Will’m de Hastinges, Or, a maunch within an orle of 8 martlets Gu a label of 3 pts Ar each point charged with 4 barrulets Az (Sir Willam de Hastings)

Sr John Hastinges son frère, Ar 5 barrulets Az a shield Or, charged with a maunch Gu within an orle of 8 martlets Gu (Sir John Hastings of Gloucestershire, brother of Sir William)

Sr John Sein John de Lageham, Ar on a chief Gu 2 mullets Or, pierced Vert, a border indented Sa (Sir John de St John of Lageham, a crusader)

Sr Amory de la Souche, Gu 10 Bezants, a bend Az (Sir Amory de la Zouche, fought at Boroughbridge)

Sr John de la Riviere, Az 2 bars indented Or (Sir John de la River of Berkshire)

Sr Gualter Gastellyn, Or, semee of billets Az a label of 3 pts Gu (Sir Walter Gaselyn of Hants)

Sr John Gastellyn, Or, semee of billets Az a bend Gu (Sir John Gaselyn of Hants)

Sr Thomas de Verdon, Sa a lion ramp Ar lang Gu (of Alton, banneret, baron 1295, crusader)

Sr John Hovile, Quartlery Or and Gules, in the 1st quarter a martlet of the 2nd

Sr Edmon de Plaicy, Ar a bend Az between 6 annu Gu (Sir Edmond de Plaice)

Sr Herbert des Mareys, Ar a lion ramp Sa lang Gu (Sir Herbert de Smareys)

Sr John de Maltravers, Sa`fretty Or, a label of 3 pts Ar (Sir John Maltravers, baron 1330, battle of Boroughbridge 1322, siege of Calais 1345-8)

Sr John de Felton le Filz, Gu 2 lions pass Ermine, crowned Or

Sr Simon de Mancestre, Vaire Ar and Sa on a bend Gu 3 eaglets disp Or (of Warwickshire)

Sr Thomas Morthet, Or, fretty Sa (Sir Thomas Murdac of Northamptonshire)

Sr John le Roz le Filz, Gu 3 lioncels ramp Ar a label of 3 pts Az (Sir John le Roos, le fils)

Sr Phillippe de Courteney, Or, 3 Torteaux, a bend Az (Sir Philip de Courtenay)

Sr Walter de Kydemor, Gu 3 stirrups Ar (Sir Walter de Ridemore/Rydemor)

Sr Robert de Boys, Ermine, a cross Sa (of Suffolk)

Sr Will’m Marmyon, Gu a lion ramp vaire Ar and Az crowned Or (Sir William Marmion)

Sr John de Norewode, Ar a cross engrailed Gu a label of 3 pts Az (Sir John de Norwoode)

Sr John Penbrige, Az a chief Gu and a bend engr Ar (Sir John de Penbrige/Penbrugge)

Sr John Sauvage, Ermine, on a chief Az 3 lioncels ramp Ar (Sir John Savage of Kent)

Sr Nichol de Hastynges, Az a chief Gu a lion ramp debruised by a bend Ar (Sir Nicholas Hastings of Gressing, Norfolk)

Sr John Maudut, Gu 3 piles wavy conjoined in base Or (Sir John Manduit)

Sr Will’m Bottetord, Gu on a saltire engrailed Ar a mullet Or (Sir William Botetourt of Norfolk)

Sr Thomas Bottetord, Or, a saltire engr Sa a label of 3 pts Gu (Sir Thomas Botetourt of Norfolk)

Sr John de Hastinges, Az a chief Gu a lion ramp Ar (Sir John de Hastang)

Sr Rauf de Camoys, Ar on a chief Gu 3 Bezants (Sir Rauf Camoyes, banneret)

Sr Rauf de Stanlade, Ar a lion ramp double-queued Sa (or Stanlowe, of Staffordshire)

Sr Robert le Fitz Rauf, Barry Ar & Az 3 buckles Gu (Sir Robert le Fitz Rauff)

Sr Edmond de Cornewaile, Ar a lion rampant Gu crowned Or, debruised by a bend Sa charged with 5 Bezants (Sir Edmond de Cornewall, fought at battle of Boroughbridge)

Sr John de Vepount, Or, 6 annulets Gu 3, 2, 1, a label of 3 pts Az (Sir John de Vipount)

Sr Richard de Bermighame, Gu 3 owls Ar (Sir Richard de Bermingham)

Sr John de Charnell, Or, a fess Ermine betw 2 chevrons Gu

Sr Thomas de Stavile, Gu a fess betw 3 escallops Ar

Sr John de Sunny de Kent, Quarterly Or and Az a bend Gu (Sir John Someri, of Kent)

Sr John Davernon, Az a chevron Or, a label of 3 points Ar

Sr Will’m Cassynges, Az a cross moline voided Or, debruised by a bendlet Gu

Sr John de Clifdoune, Or, a lion ramp Sa crowned and langfued Gu (Sir John de Clifton)

Sr Hamond de Sutton, Vert, crusilly and 3 covered cups Ar (of Essex)

Sr Will’m de Bokkesworthe, Or, a lion ramp Purp collared Ar (or Bolkworthe)

Sr John Chandos, Ar a pile Gu a label of 3 pts Az (of Cambridgeshire)

Sr John de Mounteney, Az on a bend betw 6 martlets Or a mullet Gu (or Munceni, of Essex)

Sr Estienne Hovel, Sa a cross Or, a label of 3 points of the Last (Sir Stephen Hovell of Suffolk)

Sr Will’m Tracy, Or, 2 bends Gu in canton sinister an escallop of the Las (of Worcestershire)

Sr John de Morais, Sa billetty and a cross flory Ar

Sr John de la Pulle, Ar a saltire Gu a border Sa Bezanty (Sir John de la Pole)

Sr John de Sutton, Az a chief Or, a lion ramp Gu

Sr Roger Bownd, Ar a chief indented Sa

Sr Thomas de Bermyngham, Az a bend engrailed Or (Bermingham)

Sr John de Haverington, Sa fretty Ar (Sir John de Harington)

Sr Th. Latymer, Gu a cross flory Or, a label of three points Az each point charged with as many fleur-de-lys of the 2nd (Sir Thomas Latimer)

Sr Thomas le Roux, Ermine, on a chief indented Gu 2 escallops Ar (Sir Thomas le Ronye)

Sr John Sudbury, Ermine, on a chief Gu 3 cinquefoils Or

Sr Roger Rocheford, Quarterly Ofr and Gu a border indented Ar (Sir Roger Rochford)

Explicit de la Tournay a la Ville de Dunstaple l’an de Roy Edward Filz le Roy Edward

A tournament c1300

Other copies of the Dunstable roll mention further shields, some of which cannot be identified. A Tomkinson has suggested these additional names: Sir William Clinton, John Dabernon the father, Sir John Beauchamp, Sir Edward Beaulylie, Sir Moris Barkley, Ralph Perot, ? de Rye, Sir John Mounford.

There was a group of knights from the Bedfordshire area who were at the tournament in Dunstable but who are not included in the heraldic roll prepared for the mêlée. The source for these names is a manuscript in the library of Queen’s College, Oxford, transcribed by the Rev Frederick Blades for his “Bedfordshire Notes and Queries (vol I page 33) published in 1886.

B=blue (azure); A=argent (silver)

Frembrand [of Potsgrove] — Gu. a cross or seme de cross-crosslets or. (?Nicholas Fermbaud of Holcot, Battlesden, Potsgrave)

Sr, John de Pabenham — Barry of six B. and A., a bend gu. charged with three mullets or.

Sr. John de Pabenham, son filz — Barry of six B. and A., a bend gu. charged with three mullets pierced or. (Accompanied Edward I on his Scottish campaign 1296, accused of malpractice as Sheriff of Beds and Bucks 1314, defended castle at Hertford during Earl of Lancaster’s rebellion).

Trayly [of Northill] — Or a cross gu. between four martlets gu. (Trailly?)

Sr. John Rydell — Paly of six A. and G., a bend sa.

Sr. Walter de Baa — Gu. a bend A. between three plates A.

Sr. John de Sathbury — Erm. on a chief gu. three roses or. (of Bromham)

Beauchampe — Gules fretty arg. (perhaps William de Beauchamp of Bedford)

Sr. Richard le Rous — Quarterly A. and S., a bend or. (held land at Bromham, frequently represented Beds and Middlesex at Parliament, 1297-1313; in France on the king’s service 1300; on expedition in Wales against the enemies of the Despensers in January 1322, when he was over 60 years old. His wife Joan was heiress of William de Beauchamp, baron of Bedford).

Sr. John Peyure — A. on a chevron gu. three fleurs- de-lys or.

Sr. Rauf Perot — Quarterly per fess indented or and B.

Sr. Willm. Ynge — Or a chevron vert.

Sr. Roger de Heyham — Paly of six A. and B., on a chief gu. three escallops.

Sr. John de Mortein — Erm. a chief gu.

Sr. David de Flutewike — A. three lions passant gar- dant S.

Sr. Rauf de Goldington — A. two lions passant B. (in Parliament for the shire many times 1294-1312. Died soon after 1312).

Sr. — de Wahulle — Or three crescents gu.

Sr. Piers Lorynge [of Chalgrave] — Quarterly A. and G. a bend gu. (Sir Peter Loring,of Chalgrave. On military service in Flanders 1297, in Parliament 1313-1316, “unfit for service on account of advanced age and illness” 1322. He was the grandfather of Sir Nigel Loring, hero of the battle of Sluys, one of the original knights of the Garter, and a character in the Conan Doyle historical novels).

Sr. Roger Peyure — A. on a chevron B. three fleurs-de- lys or. (of Keysoe, Little Staughton, served in Parliament 1319).

Luttrell Jousting

THE COMPLETE LIST FOR THE 1334 TOURNAMENT