Medieval Dunstable© Webmaster Helen Mortimer Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Monastic Life

by Jean Yates

The Early Augustinians

One of St. Augustine’s letters written for his sister, a nun, was adapted and became known as the Regula Tertia. This along with the Regula Secunda, a short document listing the daily services and rules on discipline and manual labour formed the Rule of St. Augustine.

This may have been in place by the 6th century but it really emerged in the 11th century in France and Italy. It had the backing of the Pope, and in England the majority of Augustinian houses followed this rule.

It is generally believed that St. Botolph’s Colchester was the first English house of the Augustinian order. Two priests from the house were sent abroad to study and return to teach their fellows and these two were Norman and his brother Bernard. They went to Beauvais and to Chartres, and then returned to Colchester in about 1104. In 1107 Norman founded the Priory of Holy Trinity, Aldgate, established by Queen Matilda, and then became her confessor.

Henry I founded five houses of regular canons including Dunstable. He established the priory opposite his palace of Kingsbury in East Street, Dunstable, and Bernard was put in charge. Aldgate claimed Dunstable as a daughter house.

The foundation date is unknown but Bernard, Prior of Dunstable, is a witness at Aldgate to a document in 1125 and Henry I was sufficiently confident in their organisational skills that he gave them the town in 1131, the details of which are in the history of the Priory.

Strictly speaking the regular canons are not monks. They followed the rule of St. Augustine, modelled their life on the apostles, but did not take the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. Their daily regimes and customs were however very similar to other orders.

When Henry I died, there were nearly 200 Augustinian houses, the highest number of any order in the country. In his reign the canons were held in high esteem and had enjoyed quite a monopoly of influential and royal patrons. Things were about to change with a flood of powerful rivals.

The Dominicans

St. Dominic received papal approval to form a congregation, and in 1217 the order of Friars Preacher was confirmed. From the 1250s they became urban based preachers and combined a sense of apostolic mission with complete poverty.

By 1260 there were about 36 houses in England, including Dunstable.

The Dominicans became very popular. They identified with the poor as being totally dependent upon charity, but they were not part of the political scene and not the tax collectors. They preached in the market place and became skilled at simple storytelling rather than learned discourse.

In the History of Milton Keynes we are told; ‘The Dominicans, the wandering friars, with their house at Dunstable, were more frequently seen in the Brickhills and along the Bedfordshire border. Perhaps their greatest year was 1292 when they preached the crusades.’

There was a conflict of interest between the friars and the canons, both vying to be the recipients of any gifts from the townspeople. Unsurprisingly the two were not the best of friends although they were close neighbours. The Dominicans did not have the churches, manors and lands of the Augustinians but neither did they have the same financial responsibilities as the canons of caring for travellers, pilgrims, the sick or poor.

A Way of Life

The regular canons, the ‘clerical monks’, served the pastoral needs of a district, or, an urban location, in a monastic disciplined way. They regarded the maintenance of hospitality in the widest sense as amongst their most obligatory duties. To some of the houses positioned in rural areas this was a simple duty, but to Dunstable situated on one of the busiest crossroads of England, this was a massive task, both in terms of numbers of travellers, and the financial implications.

In times of famine a monastery was seen as a place of refuge for the poor and hungry, and the Augustinian rules of offering hospitality to all, caused considerable impoverishment.

The Barnwell Augustinian Priory rules, or custumal, gives us what we would now call a mission statement.

‘By joyfully receiving guests, the honour of the monastery is increased, friends are multiplied, enemies confounded, God is honoured, love extended, and copious reward in heaven is promised.’

Working in and with the community, the Augustinians, very sensibly, did not lead such austere lives as some of the enclosed orders. All things in moderation was their ideal.

This applied to food as well as prayer and silence, and moderate use of meat and wine was allowed. As centuries moved on, flesh could be eaten on three days a week. On other days, fish, eggs and cheese, but these rules were interpreted differently from house to house. The eating of flesh was allowed if you were ill, but pretending to be ill to get meat was punished. Birds were not considered to be flesh and the priory owned dovecotes, ducks and geese. Wine was allowed on feast days, but usually home brewed beer was drunk. The ale was required to be of a good standard, this was to prevent bad beer being used as an excuse to visit the town and the inns.

As Lord of the Manor, the prior fixed the price of bread and beer in the town, and this depended upon the harvest. If the bakers and brewers overcharged they were fined, and if a third offence was committed the prior took all their stock for his own use. Any further offences and they were punished by the tumbril and pillory.

Meals usually comprised of two cooked dishes and perhaps a third of home grown fruit or vegetables. The Priory had its own bake-house, and a dairy where they made cheese. Pittances were very welcome in the refectory, they were small treats, extra dishes, often paid for by a benefactor.

Herbs and spices were introduced into the diet, and food improved in taste, variation and quantity throughout the period. Dunstable kept bee hives, and several canons were chastised by the bishop for selling honey and keeping the money for themselves.

The frequent royal guests would of course have eaten very differently, and no doubt be pleased that Dunstable had its own vineyard.

Dietary concessions were granted to novices and after bloodletting. Meat and nourishing food was allowed to help recovery. Bloodletting was used as a way to prevent sickness and to cure sickness. It was carried out several times a year.

Sign language developed in the monastery refectories where silence was maintained. Pulling the little finger on the left hand and mimicking the milking of a cow was one of these signs, but a visitor noted that in one priory the silence had become a dumbshow.

An Augustinian Prior who moved from Kirkham to Cistercian Woburn complained of ‘tasteless food, scratchy clothing and onerous manual labour.’

The Beauvais custom required that ‘clothing should be neither excessively elegant nor extremely mean.’ The regular canons wore linen, where most monks wore wool.

Their dress was composed of a long cassock lined with sheepskin, over which was a long linen rochet with wide sleeves. The amice was originally a short cape, but later joined at the front and put on over the head. The long cope was the distinguishing feature of a canon, known as the habit, it gave them their name, the black canons, and black was the colour of humility. Two types of cope were worn, one with a hood for outdoor wear and the choir cope for use in church.

Their dress was composed of a long cassock lined with sheepskin, over which was a long linen rochet with wide sleeves. The amice was originally a short cape, but later joined at the front and put on over the head. The long cope was the distinguishing feature of a canon, known as the habit, it gave them their name, the black canons, and black was the colour of humility. Two types of cope were worn, one with a hood for outdoor wear and the choir cope for use in church.

In the early days they slept in their habits, nightgowns being introduced later.

Rules were strict concerning modesty of dress and the novices were instructed in the correct way to change their clothes whilst hiding their nakedness. When using the lavatory the hood was to be up and eye contact avoided.

New clothing, stockings and boots were issued every year.

‘In 1295 because of the poverty at Bradborne, we granted to the brothers there our wool supplies and all our revenues from the place apart from the tithes of Brassington for that year. These tithes brought in seventeen marks for the priory’s clothing.’

It was rumoured that St. Cuthbert did not take his boots off from one Easter to the next when he got a new pair.

Bathing was not something the canons normally enjoyed. Prescribed sometimes for the sick and infirm, the healthy monk was more likely to take an icy bath to cool his passions!

In the main, the Augustinians did not believe that discomfort was a sign of godliness and this included the suffering that verminous clothing brought.

Washerwomen would have been employed, their occupation easily recognised from their blistered hands, arms and legs obtained from using soapwort and treading the washing in tubs. A mention of a tailor’s room at Dunstable tells us the canons did not do their own mending.

Tonsures were a sign that you were a monk. The shaving of heads was a communal affair and carried out in the cloister. As in other things there was a rule of who went first, as of course the last ones got the blunt razor and a wet towel. Barbers were eventually employed to reduce accidents.

The tonsure brought you status as in the annals; ‘He released the prior’s bailiff from prison, because he was a cleric, and tonsured,’ but William the chaplain of Tissington lost his job because he ‘publicly kept a mistress and hunting dogs, abandoning the tonsure and his clerical office.’

A life of self-discipline: Resist temptation, fight your demons and take responsibility for your thoughts and actions. Thoughts were to be controlled, and rules were there to help.

Sleep like food was seen as a physical need, and self-deprivation a sign of holiness. It was believed that the night was a vulnerable time when the devil preyed on monks. To lie immodestly at night was not allowed, bare flesh could draw the devil and so only arms, feet and head may be uncovered.

Fire was a constant threat with straw on the floor and candles everywhere, and patrols of the dormitory were carried out to ensure safety and of course good conduct. The dormitories in later years tended to be partitioned off as monks demanded more privacy.

The rule of chastity: Advice was given to keep temptation at bay by taking cold baths, eating no meat and not watching animals mate. It was thought that the devil may appear as a naked woman. Any meetings with women took place in the open and with witnesses.

Many restrictions were to prevent allegations and scandal. Credibility and reputation was all when it came to gifts from patrons. When away on business lay brothers or servants would always provide an escort.

Women were forbidden from entering the cloister, although as time went on benefactors were sometimes given permission, but not allowed to stay the night.

The charters in 1215 refer to ‘the shortcomings of the existing clerics; that Robert the rector of Bradbourne was son of the former rector, himself incontinent; Henry the vicar of Ballidon chapel was son of a former vicar, and also himself incontinent.’ Incontinent meant married, and this suit brought by the prior enabled Dunstable priory to institute their own canons in these churches for the first time.

Living an austere life in cold buildings with poor lighting and interrupted sleep every single night, meant a number of the monks suffered ill health. Heavy bells were responsible for back problems, an austere diet for stomach disorders; combine these with heavy manual labour and it was a recipe for mental and physical problems.

Infections were not recognised, and in hospitals people often shared beds. A bowl of water was placed on the chest to see if someone was alive, pulses were not yet known. Most illnesses were put down to divine judgment. The population of England was about five million in 1300, and only two and a half million in 1400 after the plague had taken its toll.

Eventually it was realised that a great deal of strength was needed to maintain this type of life, and leisure time was introduced. Fresh air in the countryside was considered important, and if a monastery was in a dirty urban situation the monks could obtain a better lifestyle by spending time at the manors. John Maydenbury, one of the Dunstable canons is mentioned several times in the Annals firstly when he joins the priory, and again when twice he travels to the Derbyshire manor at Bradbourne.

Canons may have been allowed some pleasures but those did not include the keeping of hawks and hounds. However, in 1430 the bishop wrote to the prior; ‘ All the canons must be present in the priory, unless they have permission and licence from the prior or sub-prior. The canons are not allowed to indulge in hunting and hawking.’ They certainly went rabbiting, and we see written references to free warren. Sparrowhawks were kept by some monks, once again there was a hierarchy, the type of bird you owned dependent upon your position in society. But it is obvious that rules were not always kept.

Daily Routines

Management - who did what…………………

Until the 1200s, the word of the head of the house, the Prior or Abbot, was law and the normal practice was not to write anything down but rely on highly developed memories. In 1234 the General Chapter insisted that every house should have its observances in writing, to aid in the instruction of the novices.

To be the father of a monastery could be an onerous task, with the constant financial burdens and fear of litigation. Being fair and not too harsh a leader, dealing with the monks fears of inadequacy and self-doubt, their crises of faith and all the problems of monastic life, combined with running a large business with offices in various parts of the country must have given the priors some sleepless nights.

Prior – the father of the house, to be completely obeyed. He had his own set of rooms. Sometimes given other responsibilities outside of his own house as a representative of the pope i.e. Prior Morins.

Sub-Prior – deputy, with the Prior often away he was called upon to make the decisions.

Obedientaries – were officials with special responsibilities

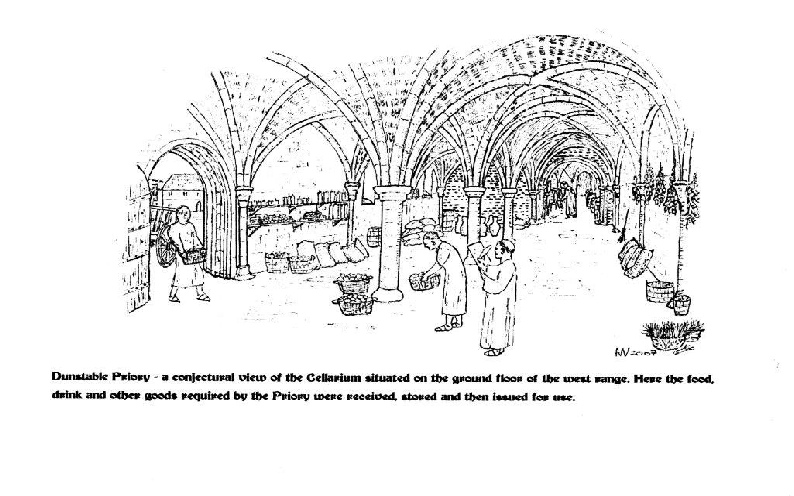

Cellarer – responsible for provisioning the house, supervision of servants, lay brethren, rents and revenues. Everything to do with food, drink and fuel, for the bake-house, the brewery and the kitchen. All transport of goods by land or water. Purchases of iron, steel, wood, ploughs and carts, clothes, dried goods and wine. He visited the manors and farms ensuring efficiency and honesty, and was often away on business. He usually had a sub-cellarer to help him.

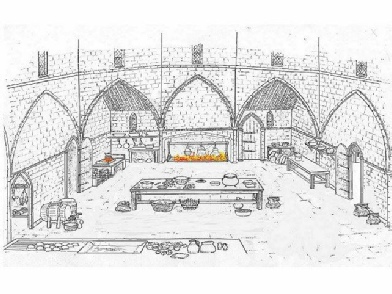

Cellarium

Pittancer – given money, sometimes from gifts, to supply extra food called pittances

Sacristan – responsible for security and cleanliness of the church, provision of vessels for the altar. In charge of lighting, he saw to making candles and issuing the various types; wax, mutton fat, tallow, or oil for cressets. A sub-sacrist was often responsible for bell ringing at correct times.

Precentor – Ensured the correct number of books were available for services, the house ‘librarian’. He also led the complicated chant in church leading the choir on the south side

Succentor – assistant to Precentor, he led the choir on the north side and had a strong voice

Novice-master – prepared postulants to take their vows. Normally a year was spent as a novice when they received training in the routines of the house and the services. It was a big decision for both parties as to the suitability of the candidate to take their vows.

Infirmarian – responsible for the management of the infirmary, and care of the sick and elderly canons who lived out their days in the priory.

Kitchener – overlooked meal preparation ensuring cleanliness, efficiency and punctuality.

Chamberlain – provided garments, shoes and bedding in the larger houses

Almoner – distributed charity and visited the sick and poor. His job was to clothe, feed and comfort pilgrims, beggars and lepers.

Hosteller – ensured guest accommodation was clean and attractive and should provide a good fire. He needed to be able to mix with all levels of society.

School Master, the bishop in 1442 comments that the school is doing well.

Officials varied dependent upon the size of the house. Recorded at Dunstable, a Cellarer and Pittancer, a Novice Master, a Chamberlain, Kitcheners and in 1442 a proud and rude cook!

There was a Prior, Almoner and Sacristan at both Dunstable and Ruxox, Flitwick, which was a cell of Dunstable.

All of the canons were ordained priests, educated men often from good families. Lay brothers helped with the work, and secular priests were appointed in 1200s to serve some of the churches, living at the vicarage in the village they served.

The introduction of lay brothers gave opportunities to those who were illiterate to join the monasteries. The lay brothers and servants carried out a lot of the heavy manual work, had their own living quarters and dormitory and area of the church.

We also learn that there was a porter at Dunstable, and the leper hospital of St. Mary Magdalene had a warden. The herbarium must have had gardeners and the vineyard would have needed many hands. Six men from the vineyard at Cadeby plus six men from the vineyard at Dunstable formed a jury in 1247.

We have a snapshot in 1400 of numbers at Dunstable.

Prior Thomas Marshall

Secular clergy – those living in the world, not in a monastery

Thomas Chamburleyn Capellano (Chaplain) Johanne Northampton cleric

Johanne Trout cleric Johanne Man cleric

17 Named Canons

Willielmus de Berkamstede Johannes South

Johannes Hoche Johannes Todyngdon

Willelmus Piel Johannes Hougthon

Willelmus Sondey Johannes Reymond?

Willelmus Chalgrave Johannes de Kayso

Willelmus Segenho Johannes Sundon

Ricardus Bokenhull e Rogerus Lytgrave

Thomas de Flittewyk Symon Bokyngham

Thomas Lowthe

It is also noted that the Prior of Dunstaple is the rector, ie ‘owns’ the villages of; Studham; where Walter was the vicar and Johannes Smyght capellano (chaplain),

Totternhoe; Nicholao was vicar, Willelmo Chapman capellano, and Willelmo de Bolewyke clero (cleric);Chalgrave; Willelmo was vicar.

In addition, at Flitwick, Symon Bokyngham is noted as vicar and Ricardus Bokenhulle as master of Rokesekes, both of whom also appear on the list of Dunstable canons. Evidence, that regular canons served the churches they owned, a matter of dispute between some historians.

Where the priory held the right to present the vicar to a church this was known as an advowson.

Where some orders had a minimum number of monks, usually thirteen, the Augustinians did not. But they did have named officials who had their own responsibilities. In the early days these obedientaries were allowed total control of their departments, deciding their own budgets and through mismanagement some houses got into serious debt. Later, budgets were controlled centrally by the house.

The annals do refer to the almoner’s own sheep and plough team of horses, but this may have been because the Priory built a separate almonry in the town, and benefactors specified the use of their gifts for the poor. But in 1281the annals tell us ‘we assigned a fixed income to the kitchen, namely the toll of the town and the market, and of the pigs on the franchise’.

Where ………………..

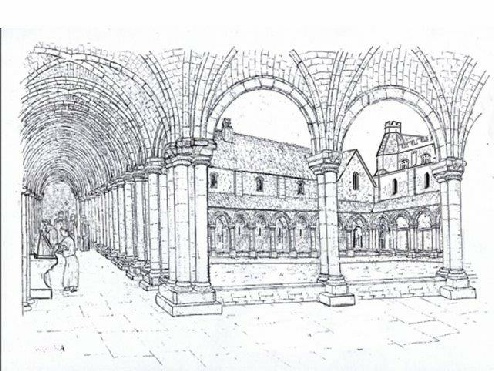

The cloisters

The cloisters; a place of quiet and contemplation the rules say. But was it? It was a busy thoroughfare, each side or alley, was used for a different function, and reading was done aloud. All of the buildings needed for daily living could be accessed from the cloister. The centre, known as the garth, might be used as the herb garden or herbarium, or for drying the washing spread on the lavender bushes.

The north cloister adjoined the church, and receiving the best light was the place for writing and illuminating manuscripts. These writing cabinets where the scribes sat, were called carrels.

The east cloister range usually housed the chapter house, parlour, dormitory, and library or book cupboard. The dormitory was upstairs and accessed from outside stairs in the cloister and internally by night stairs. The rere-dorter, the toilets, was at the far end of the dormitory. Hay was used as toilet paper and herbs to make a pleasant smell.

The whole community met in the Chapter House every day. These chapter meetings were usually held after the office of Prime at 6am. Proceedings began with a reading of a chapter of the Rule. This was followed by confessions by individuals of their faults. The Priory’s business was then discussed and tasks were assigned. These meetings were sometimes lively affairs, and an ordeal for some.

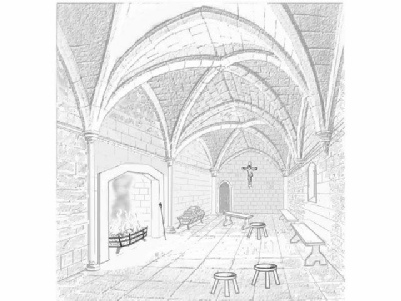

The fire in the warming house or parlour was lit from 1st November until Good Friday. At Barnwell live coals were used to warm the hands when ministering at the altar, and sometimes the barefoot processions proved just too cold and dispensation to wear boots was given.

Warming room

The cloister’s south side usually contained the refectory with a kitchen, nearby, but separate in case of fire. The lavatorium or wash basin was in the cloister and outside the refectory ensuring everyone washed their hands before entering. Although the prior had his own quarters for entertaining guests, there was a dais at one end of the refectory where sometimes he would sit at a high table.

The kitchen

In the west alley was where the novice master instructed the novices. The western range of cloister buildings was where a monastery connected with the outside world. Here would be the outer parlour where visitors were met, and where the cellarer’s supplies were kept in storerooms.

Guest accommodation could be in this area and we know that the king asked for rooms to be built at Dunstable for his own use. Successive kings visited Dunstable on many occasions and were often another drain on resources.

……………and When

Before cheap lighting, our daily patterns of life revolved around sunlight and our canons varied their routine from winter to summer. Rising at 2.30am and retiring at 6.30pm in winter, up at 1.30am in the summer, with bedtime at 8.15pm. The main meal was at mid-day, followed by a siesta, and another lighter meal about 5.00pm.

Meals were taken in silence, apart from the reader in the refectory pulpit. Silence was maintained in church, refectory and dormitory.

Conversations were allowed when they concerned the business of the priory, and when dealing with visitors. But it was considered that gossip led to arguments and conspiracies, and the advice was to sing psalms when working.

Dunstable, situated at the crossroads would have been a hotbed of gossip. Travellers and pilgrims staying at the town’s many inns would have brought the news with them. Reports of the king’s deeds, national and international affairs are all reported in the Annals. The scribe relates in great detail the siege of Bedford castle, crusades, tournaments, church appointments and deaths, the market prices and even the weather.

A bishop’s visit in about 1430 resulted in a letter to the prior instructing him ‘to ensure that all the canons retire to bed immediately after Compline. The feasting, drinking and gambling is to stop, upon ‘pain of imprisonment for one year’ if they continue. ‘Meditation must be observed in the cloisters after breakfast and after Vespers.’

Distractions were everywhere. The numbers of pilgrims visiting a shrine could be disruptive to monastic life, and as keepers of a shrine the monks’ responsibility was to protect it from theft and damage. Dunstable had the shrine of St. Fremund. Guesthouses were built well away from the cloisters, often to the west, so visitors did not disturb the monks or lead them astray.

Augustinian Services were shorter and simpler than some orders, just nine lessons at Mattins. Time was devoted more to pastoral duties and stress was put on time for reading. The Augustinian order attracted learned men, one of them being Prior Morins at Dunstable who began the Annals.

The sacrist rang the bell to rouse the canons for the daily round of worship. This must have been easier after 1293 when a very expensive and one of the earliest recorded mechanical clocks was installed, before that, someone was watching the sky to determine if it was time for the midnight office, known as Nocturn or Vigils.

Many references speak about the difficulty of rising from bed at midnight and attending Vigils. It was a sin to be late that was confessed and punished by the chapter, and it was difficult to stay awake. Peppercorns were chewed to sharpen the senses. A monk could find himself woken up in Vigils by a lantern shone in his face by the official responsible for vigilance. The lavatories were also checked for sleeping monks.

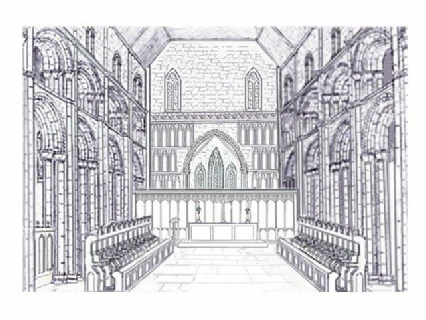

The chancel

Each office began with the Lord’s Prayer, followed by hymns, psalms and chants. The night office of vigils is followed by seven daylight offices and a daily Mass, with two masses on feast days. Lauds, and then Prime, followed by Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and then Compline brought the day to an end. Music used at Mass, known as plainsong, or Gregorian chant, developed during the medieval period. Times of the year such as Advent, Christmas, Lent, Easter and Whitsuntide together with saints days made monastic worship quite complex.

Heirarchy determined the canons’ place in the choir stall, the chapter house, in the refectory and in processions. Novices sat at a separate table in the refectory and had their own dormitory.

Work: When not in services or private prayer, the canons at Bridlington were expected amongst other things to; prepare parchment for the writers, sew new clothes for the brethren, make wooden spoons and candlesticks, weave baskets, beehives and mats, dig and dung the garden, sow seeds, trim, prune and move trees. Plough, sow, reap, mow hay with a sickle and make a haystack. This was in addition to reading, preaching, writing, and teaching. At Llanthony canons helped with building works and novices were examined to see if they had any ‘useful arts’.

Dunstable canons did not lead the agricultural, rural life at Bridlington, but would have supervised others doing this work. They had many servants working in the priory, the courtyard, the hostel, the hospitals and the farms and manors. A new hall for servants was built at one of their outlying manors, Pattishall, Northamptonshire in 1249.

Building work would have been constant. The Annals frequently mention re-building work when walls and buildings fall down. The Prior’s own stone quarry at Totternhoe, his lead mines in Derbyshire and clay pits at Husborne Crawley as well as the courtyard at Dunstable would have been hives of industry. The great barn in the outer courtyard, just behind Priory House would have housed the priory’s main food supplies.

Picking your way carefully past the barns and stables, through the geese and ducks, chickens and pigs across a muddy courtyard on a wet day with the sounds of the blacksmith, the carpenters and the stonemasons would have been a noisy and smelly business.

A vast amount of work was carried out by these urban canons. They fulfilled their many responsibilities to the community in the widest sense of hospitality from pilgrims and travellers to the sick and lepers. In addition they managed their corporate business without today’s communication network.

In The Tracts of Dunstable Priory we learn that the two secular chaplains, receive ‘from the cellarer every week the same amounts of bread and beer and pottage as two canons would receive’, and they ate with the canons in the refectory. ‘Each of them has 3d a week for relish, 20/- a year for stipend from the sacristan’, and ‘from trentals and bequests, offerings and gifts, what they have by custom’. The prior provides a house for them and this is maintained at the cellarer’s expense. They are also allowed straw twice a year to repair their beds from the prior’s granges.In addition they are given ‘every week for their attendant fourteen brown loaves, and four gallons of the second beer, and pottage of the household, and 1d for relish from the sacristan’.

A deacon and a subdeacon, ministers to the priests are then mentioned. The deacon shall be provided for by the sacristan and ’shall have every day the kitchen pottage’. He ‘shall also have from the offerings at those altars assigned to the parishioners, one farthing if 6d be found in the box; and if 12d be found be found in it, he shall have one halfpenny; and if more have been offered, he shall not have beyond one penny’. Other alms and gifts are his ‘according to the suitability of the time and his personal deserts.’ The deacon then has to provide for the subdeacon and give him a share of his benefice as is agreed. They do not receive stipends.

In return; one of these priests had the care of the ‘souls of the whole parish, and may minister things spiritual to them according to ancient custom’. The other, who was to help the first ‘ in all Offices’, ‘shall daily celebrate mass for the dead’, with a special mention of those named in the charter.

Working for the Prior or the Lord of the Manor

The peasant working for the lord of the manor, or the prior, had a pretty tough life. Piers Plowman says of a poor man, there was many a ‘winter time when they suffered much hunger and woe’.

The prior was effectively the lord of the manor of Dunstable. The 1221 custumal or byelaws survive, and we see that the burgesses of the town had important rights as well as obligations. Life was rather different for peasants.

A normal family needed almost 10acres of land to grow corn to survive, and many serfs had few acres and were obliged to perform other work on the manor.

Dovecotes became one of the most hated landmarks on a manor, with no peasant allowed to have or harm the birds. A large dovecote could hold hundreds of birds all fattening themselves on the peasants’ fields. The annals tell of dovecotes being built on several of the priory’s manors.

A grant of free warren meant that the lord of the manor could prevent anyone from entering his lands to hunt wild animals, and men, including sometimes the canons, were in court accused of poaching. ‘In 1283 the prior and Michael of the Peak, brother John Hallings and certain others of our household at Ruxox were summoned by a writ of trespass to reply in London to David Flitwick concerning his accusation that they had broken the peace by fishing his streams and fishponds by night.’

Free men paid their yearly rent and not much else was expected of them. The serf, paid his rent, and in addition paid a price for everything else he wanted to do. Collecting dead wood – a wood penny, if he kept poultry – he paid a hen or eggs for the privilege, if he sold a beast he often paid a part of the price. When his daughter married, he paid, if he wished his son to have an education, he paid, and this was in addition to the days of work that he was expected to give his lord. These days varied depending upon the time of the year, but just when he needed to be on his own strip of field, the lord would call upon every able person to help with the ploughing, the sowing or the harvest. The peasant’s obligations were two-fold, week-works, for days of work owed every week, and boon-works, performed occasionally as extras.

On some manors it was necessary to carry the produce long distances, either to the market, or to the lord’s main manor. Smallholders carried goods on their backs, those with larger holdings lent horses and carts. Carriage therefore cost nothing as the tenants had a duty to work for the lord.

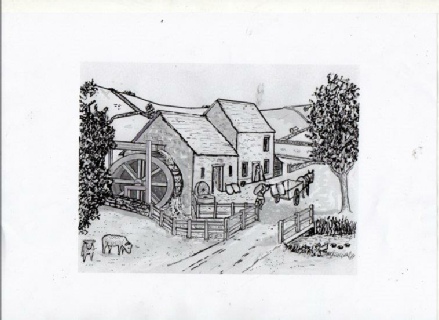

Flitwick mill

Peasants could not choose where to bake or brew, or where to grind their corn. The mill, usually a watermill was owned by the lord, his peasants having no option but to use it, and paying to use it. Flitwick mill was originally given to the priory but after squabbles amongst the family they lost it. It was so important that it was bought back by the priory in 1240, ‘which was worth more than three marks to us, annually.’

The serf also paid tallage and heriot. Tallage was a tax, variable in amount and frequency and in 1299 some serfs asserted ‘they would rather go down to hell than be beaten in this matter of tallage.’

Heriot, was the lord’s claim on property after death, and the church had a claim known as a mortuary. An old custom was to return to the lord on death, the war gear, which the lord had originally supplied, or was owed in heriot. This consisted of horse, harness and weapons. When in 1296 Sir David Flitwick died, the prior received his ‘palfrey, (horse), and his armour in death duty owed to the church’. Peasants also paid heriot, usually the best beast or chattel.

After death, the peasants’ land reverted back to the lord, but often the family were allowed to remain after they had appeared at the Manor Court and paid the ‘gersuma’, the ‘entrance’ fee.

Income and Economy

The sources of income for the Priory were many and varied as we have already seen. Travellers availing themselves of the canon’s hospitality were expected to pay something for it, or leave a gift. One man certainly did, Gaufridus le Cauceis gave them ‘the parish of Bradbourne in Derbyshire with all of its chapels, for the support of the hospice, because the canons were placed on a public crossroads of England, and had many guests’. This parish with its chapels and thousands of acres of arable and sheep grazing lands, was the most valuable gift, second only to the original endowment by Henry I of his town.

Guest accommodation was ruled to be good and clean as then the guest was more likely to make a generous donation when he left.

The main sources of cash to run the priory were from rents for the manors, farms, watermills, shops and houses. An entry fee, the gersuma, was often paid at the start of a rental, and payments made on quarter days.

Much of the Priory property was acquired as gifts from wealthy benefactors. Henry I had included Totternhoe quarry as well as the town in his endowment and other profitable gifts followed.

The manors of Cadeby, Newbottle and Charlton were given by one man, Morinus le Pinu who was required to surrender his lands when he entered the Priory as a canon. Others left their belongings to the Priory when they died, usually with conditions that masses were to be said by the canons for their souls, ‘in perpetuity.’

Watermill

In the 1200s, Greenfield Mill was rented to Woburn for 26 shillings a year and Dunstable Priory rented Lee Mill in Derbyshire for eleven marks, (146shillings) for ten years. The Priory purchased Flitwick mill in 1240 having been given it some years earlier and then lost it.

From spiritual sources, income came from indulgences, corrodies, burial fees and pilgrims.

Indulgences in medieval times promised days of freedom from purgatory, usually in return for money, although Alice Durant’s coffin lid mentions 40 days of indulgences for those saying Our Father when passing by.

Corrodies were a form of pension or insurance. A corrody could be bought from the Priory, and in return for money/gifts paid now, you would be cared for by the canons in later life, and given services after death. In the Annals it states ‘we were heavily burdened with annual corrodies and other things’.

North Marston, Buckinghamshire, a Dunstable Priory church, contained the shrine of John Schorne the rector, from when he died in 1314. The reputation that he and the nearby well could cure the sick, resulted in many pilgrims.

How annoyed the Priory must have been to see this source of income disappear when the Dean of St George’s Chapel at Windsor, wanting pilgrims, obtained permission from the Pope to transfer John Schorne’s bones from North Marston to Windsor. In 1480 the advowson, was transferred from Dunstable to the collegiate church of Windsor.

The Prior ran the town. Tolls were paid on everything coming to the market to be sold. A grant in 1203 to hold a three day market in May every year in addition to the weekly markets on Wednesdays and Saturdays was a welcome gift from the king.

The monks at Woburn paid eight marks to the Priory, followed by a rent of three shillings a year, to be freed from paying the market tax at Dunstable.

Sheep and fleeces were incredibly important, with wool being England’s major export at this time. The Priory ran its own sheep both locally in the Chilterns and on many of its manors.

‘We sold a sack of good wool at Dunstable for a hundred shillings and forty pence. For all the good wool sold we received the sum of forty and a half marks. The rough and inferior wool we sold altogether for nine marks’. 1242 Annals

A sack of wool was a statutory measure consisting of 364lb, or 26 stones. A stone weighed 14lb (6.35kg) A mark was two thirds of a pound.

Today we could interpret this as a sack of good wool, ie. 165kg, sold for approximately £3,100. One pound, (twenty shillings,) in 1270 is today worth about £600.

When money was short they sold the wool in advance to the merchants, sometimes for several years, and this speculation on the futures market often resulted in a loss.

Owning lead mines in Derbyshire must have brought a good cash income as the Prior in 1305 took Roger Bradbourn, lord of the manor, and five others to court for mining lead on his land.

The Prior had the right to hold court in Dunstable and for some years in addition to Bedford, an extra Assize court was held here. The prior received the fines. He also had his own pillory and gallows!

From The Tracts, (17). King Edward to his Justices Itinerant, for allowing the privilege of the prior; “It has been showed to us on behalf of our beloved prior and convent of Dunstable that - though they are privileged by the charters of our ancestors, kings of England, to the effect that moneys arising from all pleas and fines of their men and others who come within the burgh of Dunstable belong to the prior and convent…… and because we would not wrong the prior and convent in this matter, we order you, if the fact be such, that you then hold the pleas that concern them and their men within the Liberty of that church”.

The great tithe barns were for collecting the large tithes (tenths) of sheaves and grain. A tenth of lambs was also exacted, and the small tithes of milk and eggs, were often given to the local vicars along with altar offerings. Agricultural returns were very dependent upon the weather and harvests were often poor.

The prior received all tithes from land which belonged to the church. In Dunstable this was from four tillages around the town. He took tithes of flax and hemp, but Prior Richard waived the tithe of gardens in his time. There was a dispute between prior Richard and some of the burgesses as to tithes of a certain windmill, and of hay and of commerce. The argument was long, but eventually a friendly agreement was made. In Dunstable’s neighbouring parishes the prior took the tithes of milk and wool.

Tithes should not be confused with tithings. All men by law belonged to a tithing, a group of ten men, who were collectively responsible for each other’s behaviour. At the court of Frankpledge this behaviour was enquired into at Dunstable.

The ‘articles to be enquired from each tithing’ are detailed in the Tracts of the priory: “Whether outlaws have returned, and by what warrant. And of those who received them, and of their chattels: Whether any have absented themselves before the coming of the Justices, or before the view of frankpledge: Of murder: Of homicide: Of robbery: Of burglars and those who received them: Of men suspected and of misdemeanour such as theft or detention of moneys: Of treasure, arms, or any kind of metals found: of the taking of a waif by one who has no right to take it: Of brooks diverted, dykes unlawfully raised, walls houses roads and paths diverted lessened or obscured: Of false measures such as bushels gallons ells weights, whether they be consonant with the assize: Of encroachment made. Of receiving stolen goods: Of those who have harboured strangers, contrary to the law of the vill. : Whether they know any one of the tithing to be in the burgh who is not here: Whether they know anyone to dwell in the burgh who is not here in the assise. No action on the assise of bread and beer, because the prior’s bailiff is of the court, and the court takes or can take fines for this, as was agreed between the prior and the burgesses. And note that the whole burgh of Dunstable is the fief of the prior, as we said above; nor had any other religious body ever a fief or free tenement therein, except the Friars Preachers, who came in by special favour on the terms that they should not enlarge their site”.

The townspeople resented the hold that the Prior had over the town and their lives and the taxes imposed upon them. This resulted in a number of disputes, when concessions were given and then withdrawn, and also the 1221 Byelaws. One of which states, ‘If any man be killed or flees because of a criminal act his goods shall be forfeit to the Prior.’

The Prior was not able to keep all of his income, even in medieval times the kings levied their taxes.

Where was all of this income spent? Dunstable Priory was the equivalent of our modern day social services, responsible for providing care for the sick and poor, for travellers and pilgrims. The canons went without themselves, sometimes on half rations, to meet their responsibilities to the community and their animals when harvests were poor.

Occasionally the Priory records give us a glimpse of the current values of their property, often when the king is looking to raise revenue.

Henry VIII in 1534 decided to impose a new 10% tax on the income of all church lands and offices. A survey was subsequently carried out of all church property and revenue, known as Valor Ecclesiasticus. These records show a total per village or manor, sometimes detailed as spiritual and temporal values. There follows a few examples of the many places where Dunstable owned property:

Bradbourne rectory in the Derbyshire Peak district shows a value of £42, Pattishall rectory and tithes £13, Weedon Bec tithes (except vicarage) £12, and Stoke Hammond manor and land at Chelmscote and Soulbury £3.

Undervaluations were common, but those priories valued at under £200 were the first to be closed in 1536. Dunstable was amongst the larger ones dissolved in 1540.

Monastic Life captions for illustrations

1 An Augustinian Canon from a brass rubbing

2 Cellarium where the stores were kept (AW)

3 The cloisters (AW)

4 The warming room, the fire was lit from November until Easter (AW)

5 The main kitchen (AW)

6 The Chancel where the canons held their services (AW)

7 A medieval watermill (AW)

Flitwick – covers all pics

There's been a mill at Flitwick since before the doomsday book. The latest buildings date from the 1720s although older timbers can be seen here. These were integrated into one structure by the Victorians. Electricity and steam seriously undermined the economy of flour milling in the UK and Flitwick Mill eventually went out of business in 1987.Most of the 9000 watermills in the doomsday book were simply demolished, Flitwick Mill is being sensitively converted into a private dwelling. Photos www.flitwickmill.co.uk"

| Archaeology |

| Audio Guides |

| Education |

| Exhibitions |

| Events 2013 |

| Physic Garden |

| Priory History |

| Priory Churches / Lands |

| Town History |

| Virtual Tour |

| Website |

| Archaeology |

| Charters & Bylaws |

| Eleanor Cross |

| Famous People |

| The Fraternity |

| Friary |

| Guided Tours |

| History |

| Inns |

| Dunstable Treasures |

| Kingsbury |

| Middle Row |

| Royal Visits |

| Sheep & Wool Trade |

| The Town |

| Friary Archaeology |

| Bone Study |

| Friary |

| Annals Charters Valor Ecc |

| Archaeology |

| Churches and Lands |

| Guided Visits |

| Audio Guides |

| History |

| Monastic Life |

| Virtual Tour |

| The Augustinian Priory |

| The Canons Route |

| Bedfordshire |

| Buckingham |

| Derbyshire |

| Nothamptonshire |

| Hertfordshire |

| Leicestershire |

| Oxon |

| Priors |

| Annulment |

| History |

| Archives |

| Book Sales & Shop |

| Exhibitions |

| Guided Walks |

| Heritage Talks |

| Physic Gardens |

| Schools |

| Tourist Information Centre |

| Tea-room |

| Visits |

| Priory House Heritage Centre |

| Education |

| Knight |

| Search Results |