Medieval Dunstable© Webmaster Helen Mortimer Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

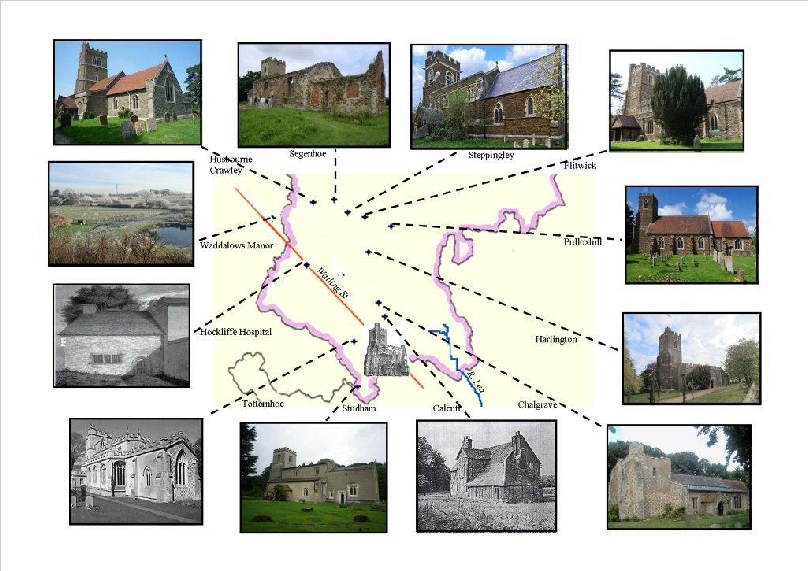

Churches and Lands

Bedfordshire

Click this link for an interactive map of the counties, towns and villages.

by Vivienne Evans

Introduction

Like all religious orders Augustinian canons (ordained priests) had three legal obligations: prayer, hospitality and the giving of alms. In most houses, including Augustinians, who were not situated on a main road, prayer was far the most important, but the Dunstable canons, situated on one of the busiest crossroads in the country were overwhelmed by the call for hospitality. From royal parties making regular over night stops and occasional formal Christmas visits lasting over a week to vagrants and the unemployable disabled who were constantly on the road. Bishops and occasionally, archbishops, and officers of the pope always stayed at the priory. In later centuries judges and their retinues and members of parliament on their way to Westminster all expected hospitality. On what must have been a daily basis the great landowners, their families, staff and tenants would have broken their journeys as they passed from one part of the country to the other.

As the years went by, crusaders, Knights Templers and Hospitallers passed regularly through Dunstable on their way to the Holy Land. In season, parties of pilgrims would have been regular visitors. The canons were unable to make a formal charge for any of these. Some paid, some made gifts and some, possibly those who were regular visitors made gifts of land or even a church from which the canons were able to draw income. The people of Dunstable made many gifts often to help with the almonry where poor visitors made no payment at all or to the leper hospital. Wealthy farmer, Alexander Young even paid for one of Dunstable’s first vicars. Quite apart from local support and the ‘payment’ for hospitality the priory received hundreds of gifts – large and small. There were many reasons why people would give their church or other possessions to a religious house. The overwhelming one was probably a sense of panic as, at the end of their life, the thought of purgatory in the future reminded them of their bad behaviour in years gone by! However there were other reasons which are well illustrated by the many gifts received by the priory.

As the years went by, in common with many others in a similar position, the priory built inns on their boundaries facing the main road. The George and the Saracens Head faced on to South Street and a rebuilt Saracens Head still stands today. They also allowed their tenants to build commercial inns, mainly in North Street. Possibly because of this the priory gradually had more need for money than food and increasingly let out their farms (and their churches) for money. The prior signed the papers dissolving his house on January 20th 1540 handing over all his land and other possessions to King Henry. However by this date, many of these had been leased to tenants; several of them being relatives or friends.

In the year 1541/2 a complete rent list was made of all of King Henry’s Bedfordshire possessions; both previously owned and as a result of the dissolution. These were administered from Ampthill Castle by the Court of Augmentation. The 1541/ 2 rent list published by the Bedfordshire Historical Record Society [BHRS Vols 63 and 64] is an invaluable help in the study of land holding in Bedfordshire at this period.

The Hospitals of St Mary Magdalene, Dunstable and of St John the Baptist, Hockliffe

It is doubtful if the gift of the Hockliffe hospital was of financial benefit or an addition to the priory’s existing social responsibilities.

In early medieval England while leprosy was still a frightening disease, lepers and other obviously sick people were not allowed to pass through the centre of towns and villages. A responsible lord of the manor would provide accommodation on their boundary and a route would be marked out taking the sick travellers around the centres of population. In 1208 the priory completed their leper hospital on the southern boundary, on the corner of what is now Half Moon Lane and High Street South. It was dedicated to St Mary Magdalene and was intended for ‘lepers and other sick people’. Roger the Chaplain was appointed as warden. His duties were ‘spiritual care and custody’ of his visitors. Although he was allowed to have a chapel and could celebrate the divine office every day there were strict rules to make sure that his chapel did not draw worshippers and their money gifts away from the priory. He was allowed to have a graveyard but only for the people connected with the hospital. As the years went by leprosy died out in England, and the travellers who stayed at these hospitals were less likely to be infectious, and they became more of a caring hostel, for very poor as well as for sick travellers. Some of the local people tried to use them as chapels of ease and in Dunstable and Hockliffe there were strict rules to make sure that their tithes and offerings went to the churches. After the dissolution the Dunstable hospital was preserved and was still being used as a district hospital in the 17th century. Although generous gifts of land were made to help cover the costs of these hospitals as there was no question of payment for accommodation the costs must have been high.

St John the Baptist, Hockliffe In 1086 Hockliffe was part of the scattered estates of Azelina, widow of the late sheriff of Bedfordshire and at her death it passed to the new sheriff. It is likely that by 1200 their tenants were the Malherbe family at Houghton Conquest and at some unknown date they took the responsibility of providing a hospital on their border with Tilsworth. The actual boundary was a stream which would have been a source of water. The religious houses were very strict about hygiene and sanitation but on the tithe map of 1839 there appear to be two parallel trenches or drains leading from the buildings into the stream! The actual building was beside the main road, represented today by Hockliffe House. The outer wall of this kitchen is built of Totternhoe stone and is all that is left of this medieval hospital. The Malherbe family would have had no intention of financially supporting this hospital. At its foundation they gave land to provide it with an income. This map of 1839 identifies enclosed land immediately behind the building which may have been part of the original gift. They also had land to the north of their building and strips in the common fields.

Whereas at Dunstable the senior priory representative was referred to as ‘Warden’ the man in charge of this semi- independent hospital was referred to as ‘Master’. He was appointed by the Bishop of Lincoln and appears to have been responsible for the land and finances as well as any staff he found it necessary to employ. The first recorded master, Adam occurs in 1248. It was not a popular position; several masters left within twelve months. There are references to ‘the brethren’ who in 1310 “……… had been unwilling to obey him [the master] and were filled with a spirit of rebellion, and that a certain lay brother had laid violent hands upon him and used contumelious words refusing to recognise his authority”. This suggests that the hospital was staffed by a small group of religious trained personnel and there must also have been an ordained chaplain, because to help with their expenses someone gave money to chant masses for their family. There was a terrible fire in 1290 and their buildings were destroyed; they took many years to rebuild. The Bishop of Lincoln pronounced that the for the next five years if local people or travellers along the Watling Street made gifts towards the rebuilding they would receive twenty days off their time in purgatory,“…… gifts were not only inspired by a sense of social conscience. They were also a by-product of the fear inherent in the pressures of medieval Christianity. On the one hand, a fear of receiving spiritual punishment, meted out as a disease, so thanksgiving was offered for avoiding or recovering from an illness or epidemic. Secondly, there was the fear of purgatory. It was believed there are three stages of after-life. Perfect souls went to heaven, the irredeemably wicked to hell, but most went to purgatory to purge their sins, …….This time could be shortened, either by good deeds (e.g. gifts to the hospital) or via the prayers of others after one’s death”. This is a quote from the booklet of ‘Wellsprings at Hockliffe House’ by Paul Bowes in 1999 at a time when Hockliffe House was once again offering hospitality of any faith or none at all.

Masters came and went and maybe the priory was called in to help before 1400. Master Richard of Dorset who was appointed in 1356 stayed on until 1400 which suggests an unusually long stable period. During his time young canons from the priory definitely visited the hospital because there was a wrestling match which got out of control and one of them was killed. However sometime during the 15th century responsibility at the hospital and its land were handed over to the priory. By this time there were “60 acres of arable land, 3 acres of meadow and 3 acres of pasture enclosed with hedges and dykes”. It was more of a hostel than a hospital but being on a main road was probably kept busy. There was no question of keeping it open after the dissolution and it was transferred to the king. A Thomas Osburne is entered as having been the priory’s tenant since 1534 and the description of hospital and ‘houses in the village of Hockliffe’ suggests that they owned some property as well as the mixed agricultural land.

The Church of St Lawrence, Steppingley

The name Steppingley suggests an early settlement in a clearing in the woods and to this day it is a small attractive village surrounded by farms and areas of woodland. One of the smaller holders of land in 1086 was the Speke (later Espec) family. Far from being one of the great Norman overlords they were here to build up their estates. They had fifteen small and very small holdings scattered around Bedfordshire and made [Old] Warden and the adjoining Southill and Northill their headquarters. As professionals rather than great landowners the next generation were helping to administer an area of North Yorkshire and were based at Helmsley Castle. While he was there Walter Espec founded the Cistercian abbey of Rievaulx and then in 1135 a second abbey on his estate at Warden. As Walter had no male heir, only daughters, his scattered estates, which included Steppingley became known as the Barony of Warden. Their isolated village of Steppingley was particularly badly damaged when King William’s soldiers passed through in 1066 and they appear to have left the care of it to their tenants. The first we hear of the church (St Lawrence) is 1166 when Richard of Steppingley gave it to the priory. Unlike some other families, his son, in 1200 and his grandson, confirmed the gift without any disputes. Despite this, of all their churches, this maybe was the one that caused them the most trouble. Undoubtedly a small amount of land must have come with the church but there are no references to any further gifts of land. It was a village with a very low population and the church would have had a very low income. When Richard of Steppingley made his original gift it was confirmed by the Archdeacon of Bedford who instituted the prior as ‘parson’ of the church. At that period ‘parson’ meant the same as ‘rector’ giving him, on behalf of the priory, the church, church land and tithes. Future events suggest that in this case it included the advowson.

There are very few more references to the Steppingley family. Fairly early in the 13th century a Roger Steppingley married the co-heiress of nearby Eversholt and they gave small gifts of land in that village to the priory. An interesting gift from Eversholt was from Roger’s mother-in-law around 1200, it was to ensure that if she died within 10 leagues of Dunstable they would convey her at their charge and bury her in their cemetery. When Roger died she took as her second husband “Adam of the Church” at Steppingley. There is no mention of a vicar at the time of Richard’s gift so this is an intriguing entry. It may just mean by or near the church or it may suggest at some level a married priest? Later entries confirm the priory’s decision to let out the position as rector for money. In 1220 there is a court case brought by their vicar, Richard, complaining that he had not received the land or money promised to him. The priory won this case but co-incidentally, amongst the published charters is ‘A catalogue of letters Apostolic in favour of the Priory’. In brief the pope is asking a group of very senior church officials to look into complaints made by the priory and others. Many of these complaints, without naming parishes or clergy, concerned vicars who “were keeping women in their houses to the scandal of the people”. Steppingley was not named until the end when their vicar “R” is accused that he refused in person to take the services.

This was all happening around 1220 and the Richard to whom the priory leased the rectorship in 1248 is undoubtedly another man. When in the same year, the vicar at Pertenhall Church died they also offered that living to Richard but he had retired as a sick man to the Augustinian house at Newnham (Bedford) and died before he could take up the livings. How or why is not recorded but the priory then let out the rectorship of tiny, insignificant Steppingley church to one of the pope’s officers. To quote the annals in 1248 “They presented a Roman called Peter Vitella de Ferentino as rector of Steppingley”. Vitella appears to have been abroad at the time but he soon came to England and stayed at the priory. For him this was another (but tiny) source of income; once it was sorted out he was going to return to the pope at Lyons. While in Dunstable he “farmed out” his church at Steppingley for five years to Gilbert of Tingrith at £5 per year. However before he rejoined the pope he appointed canon Simon of Eaton as his agent. Apparently it was three years before Simon and Vitella realised that neither of them had received any rent. This started a long legal dispute at the end of which Gilbert of Tingrith paid some of the money owing which was shared between various people. The Archdeacon of Bedford received part of this money which he used for charitable purposes. One of these was to pay (Dunstable) Canon Roger of St Albans to make three windows in the chancel at Steppingley church and to repair the church ornaments. As his first choice of rector had obviously failed Vitella came back to England and this time left the church in the hands of ‘Benedict the Priest’, again for £5 per year. It seems likely that Vitella was a member of an important Italian family but at the moment we know nothing more about him. The position of rector was once again in the hands of the priory. Sometime before 1282 they offered the position to a Richard Inge who refused it and then to a physician, Robert of Lincoln.

Our direct Dunstable sources then run out but in 1273 they appointed as rector, Master John Schorne. This was a truly, holy man who may deliberately have chosen this quiet little church for the opportunity it gave him for private prayer and meditation. Legend has it that his knees became hard and horny because of the hours he spent at prayer. He appears to have taken the services himself without appointing a vicar and so got to know his parishioners and their problems. Knowing their general health and living conditions he was often able to help cure their health problems – especially gout and similar painful conditions. The local people were amazed and even spread the word that he had cast out a demon and imprisoned it in an old boot. This may account for the pub name, The Boot, across mid Bedfordshire. So well known did he become that he was persuaded to leave Steppingley and move to North Marston, Bucks., where his story is told in more detail later in this chapter.

By 1541 nearly all the references to Steppingley name it as the “King’s Park of Steppingley” and there is a note that in 1532 £1 was spent to buy hay “for the sustenance of the royal animals in the park of Steppingle”. The only reference to the church was one sum of 6s 8d to be kept for the vicar. This suggests that right up until the end the priory had let out the rectory.

Houghton Regis with its [Church of All Saints] and its Manors of Thornbury and Calcutt

Calcutt Manor came to the priory as a royal grant by the king and as a result of armed revolts by one of the great Norman landholders.

Houghton Regis Village Three quarters of the approximate 450 acres which made up the town of Dunstable until the 20th century was taken from the royal manor of Houghton, the other quarter came from Kensworth. In compensation for their lost land the people were given Buckwood (Beechwood) near Markyate. The surviving part of their access route survives in the lane known as Wood Way near the Saracens Head, Dunstable. The remaining manorial land included Sewell and stretched up to meet the Chalgrave boundary and across to the Luton boundary near today’s Poynters Road and the Caddington / Watling Street boundary near Manshead School. Although at 1086 a great deal of this was wasteland the influence of its new neighbour meant that it was soon developed for agriculture. When in 1131 King Henry gave his new business centre into the hands of the priory he added various other privileges including the right to graze their livestock in the woods and pastures of Houghton. This was fine all the time that the king or his representatives were lords of the manor. The trouble started when Henry II granted it to a Norman baron called Hugh de Gurnay. Gurnay’s main estate lay on the border of Normandy and France; an ideal position for stirring up trouble. Houghton Regis Manor was part of a parcel of gifts intended to ensure his loyalty but without any explanation a series of entries in the annals suggests that it had been given to the priory. First, in 1203 the king had given them ‘the whole of the manor of Houghton’, then, in 1206 they were ‘deprived of their land in Houghton’ and in 1212 they had now ‘recovered their land in Houghton’. These statements actually record a series of the Gurnay family revolts against King John resulting in the confiscation of Houghton Regis followed by its return when they received a pardon. This situation was very distressing for the priory. Eventually they refused to withdraw and actually took over the manor house to the north of All Saints Church.

Thornbury Manor In response to this the de Gurnay family sent armed men and took it back by force. In fact “he uprooted the chief house to its foundations and built himself a house at Thorn”. This was the origin of Thornbury Manor which would follow the same descent as the main manor. The site of the moat is still visible on private ground.

All Saints Church The recorded history of Christianity in this village goes back an exceptionally long way. The name ‘Bid-well’ Hill comes from two Saxon words – the name of the Irish saint, St Brigid who died c542 and a spring of water or ‘well’. When the priory was in a land dispute in 1225 it was referred to as ‘Holewellehulle’. There is a chance that there was an even older Christian site to the right of the hill leading up towards Chalgrave where the Manshead Archaeological Society found Roman tiles marked with Chi Rho or Christian symbols. As a royal manor some Saxon king gave approximately 60 acres, from his own land to support both a church and a resident vicar, however after 1066 this church land was taken from the church and given to one of King William’s staff – ‘William, the King’s Chamberlain’. It then passed to his son and the church was still neglected. When in the 1120s this land was added to the vast, scattered estates given to Henry’s illegitimate son, Robert Earl of Gloucester, he then rebuilt the church. In 1153 Earl Robert’s son, Earl William, granted All Saints Church, its land and tithes to St Albans Abbey. Apart from various disputes concerning tithes the priory had no connection with All Saints. The rectory and all its lands appear in the 1542 rent list under the heading of St Albans Abbey.

The Manor of Caldecot later Calcutt The ‘Tracts of Dunstable’ a late 13th century record of the Priory’s property in Dunstable and Houghton Regis has been published as BHRS Vol XIX. This makes it clear that on at least one occasion King Henry II had given the whole manor [of Houghton Regis], with all its privileges, to the Church of St Peter Dunstable. They refer to the problems with the de Gurnay family, the ‘uprooting’ of the manor house and their move to Thorn. They then go on to explain the reaction of the priory and how on 12th November 1225 that de Gurnay had conceded the messuage (farm and buildings) called Caldecot and one third of Buckwood. The other defendants all gave at least part of the priory’s demands and a tenant William Linley ‘gave’ a farm house with 120 acres of land for a money rent and customary services. The following are of interest as they set out the meaning of the ‘customary rights’ – “one ploughing on the fallow in summer for one day, and a second ploughing in winter for one day, with as many beasts as he has in his own plough; one reaping in autumn for one day with as many men as he has at his own wages and a second reaping for one day with one man only, the prior finding his food ………”. Rather cleverly de Gurnay tried to get the prior to surrender the royal charter by which he held these privileges and accept another from him; the prior refused. In addition, to clarify the actual land etc. to which the prior was entitled de Gurnay had all the ploughland and meadow measured and acknowledged that one third belonged to the priory. Also when they decided how many beasts should graze in any one pasture a third of them should belong to the priory. When trees were lopped in the spinney adjoining Chalgrave the tops of the trees should go to the priory. He even gave permission to divert a brook so that it ran through the main enclosure at Calcutt. Following this the quite wealthy tenants on the manor added their gifts of land, houses and rents. There were small gifts but most were of several, sometimes scattered, acres e.g. around 1230 Robert Scott gave 5 acres in one piece while Richard’s son, Robert of Sewell gave 2 acres “lying dispersedly in the North and South fields of Hocton”. About the same time Ralph, son of John of Hocton gave 3 acres to pay for his funeral. There were many more gifts of land and houses and what it amounted to was that although the descendents of the Gurnay family were lords of the manor of Houghton, and St Albans had their own estate connected with the church, the priory ended up owning far more than one third of the village. They ran this from what became their manor house at Calcutt and they carefully recorded in the Tracts that it became the manorial centre not just for their scattered land at Houghton but also for their land at Wingfield, Studham, Totternhoe, Wadelow and even the one farm they held at Chalton.

Over the years there were occasional flare-ups between the two manors but Calcutt still had manorial status when King Henry VIII granted it to Urian Brereton and his wife Joan.

The Church of All Saints, Chalgrave, Tebworth and the Manor of Wingfield

Albert of Lorraine came to England as chaplain to King Edward (The Confessor) and was given the manor of Chalgrave which included Tebworth and what would become known as Wingfield. Because of this he was able to hold onto it when the Normans arrived in 1066. Although he would have spent much time at court he had a small moated manor house built and possibly rebuilt the church of All Saints nearby. His direct descendents are not easy to trace and the sheriff of Bedfordshire became ‘overlord’. Then sometime just before 1177 Simon de Beauchamp of Bedford Castle confirmed a grant from Roger Loring to Dunstable Priory giving them Chalgrave Church. It appears that the vicar had either died or recently retired and it is probable that the services were taken by canons from the priory until October 1220 when the Bishop of Lincoln dedicated the church and ordained a vicar. The glebe land is described as “two crofts and a garden next to the church”. This was a total of about 5 acres which was quite a generous endowment. However the Lorings added another half acre in one of the open fields. When Roger died he left the priory another generous gift of land and later members of the family did the same. The canon recording the charters put one group together as ‘Wingfield’.

The Manor of Wingfield Once Wingfield was established as the land of the priory lesser gifts followed and tenants of the Lorings gave them their right of tenancy; some of these were quite small, others much larger. Such gifts were intended to bring spiritual benefits. Ralph of Chauri granted various small pieces of land in Wingfield plus, at his death, a third of all his chattels live and dead in order that “he may partake of all benefits of the Priory Church” – probably an entry on the prayer roll. The Lorings continued to take a great interest in the priory. Sometime around 1230 unless needed they were relieved of the duty of attending all the meetings of the manor court and their land at Wingfield became a manor in its own right. Twice a year the priory held their main court meetings at nearby Calcutt which their tenants of Wingfield had to attend. At the Chalgrave court on the 21st May 1293 there were complaints that the prior’s men had occupied a certain common way, possibly grazed tethered sheep or tried to grow a quick crop like beans. Also they had widened their ditch in Wingfield to the harm of their Lord (of the manor) and the whole community. This may have been to improve drainage or it may be because mud remaining from the bottom of such ditches was recognised as valuable fertile soil. In either case they had made it impossible for other farmers to cross from one part of the field to the other. It appears that the division of these lands did not always run smoothly. At Chalgrave Manor Court in 1293 there was another complaint that men working for the priory found a Chalgrave tenant ploughing an enclosed area they considered to be their own and “beat him and led away his ox”! BHRS Vol XXVIII

Over the years there were several similar complaints but not usually involving violence. These disagreements may have been because there were an unusually large number of free tenants in Chalgrave.

In 1273 Peter (III) Loring was granted the right to found his own chantry chapel within All Saints church. The piscina (a draining stone basin) of this chapel can be seen to this day. When he died in 1286 an entry was made in the priory annals “He loved us more dearly than all his ancestors”. Sir Nigel Loring was the last of this important family to live at Chalgrave. He was a famous soldier and friend of King Edward III (see Town chapter) and also a founder member of the Knights of the Garter. Loring retired to Chalgrave and died there in 1386. He requested to be buried next to his wife at the priory but evidence suggests he was buried at Chalgrave. When Sir Nigel died he left two daughters as co-heiresses. One of them married the son and heir of adjoining Toddington Manor. From then on the manor of Chalgrave including Tebworth was managed from Toddington. The priory founded a Chapel of Ease at Tebworth but at first there were complaints that no one turned up to take the services. Things settled down and appear to have run smoothly during later centuries. The people of Chalgrave continued to live in Tebworth and Wingfield with Chalgrave being the site of the parish church. It appears to have been kept in a good state of repair, the chancel, and other parts being rebuilt about 1300 – 1330 and the west tower in 1380. Amazingly some of the wall paintings are thought to date back to the 13th century. Two good table tombs with effigies can be seen in All Saints church today. One of them is of Sir Nigel and the other of an unnamed member of the Loring family. There is a very good guide book available which points out how much of the work carried out by the priory can be seen today.

The Rectory of Wingfield Although it was still known as the parish of Chalgrave, in 1537 the priory leased what had become known as ‘The Rectory of Wingfield’, to Thomas Hobbes for £18 per year. This lease did not include the advowson or tithes of chopped wood or fallen trees. It did however include “Chalgravebury and fines of the copyhold court”. It had been leased for 14 years but by 1542 had become part of the royal estate based at Ampthill.

The Church of St Peter Flitwick, The Cell at Ruxox, The Church of St Mary Husborne (Crawley) and the Manor of Crawley

Following the Norman Conquest the same family held Flitwick and, what became the church end of Husborne (Crawley). One of the first references to the two churches is in the 1170s. When Gilbert Sanvill confirmed his father Phillip’s grant to a place where “the brethren serve God” (Ruxox) their own chapel of St Nicholas and a water mill plus the parish churches of Flitwick and Husborne. Also included in this gift was the right to graze their animals on the shared common land right across the village. However this gift did not go smoothly; although, Gilbert’s son had confirmed his father’s gift, after the death of his father he changed his mind and demanded that the canons of Ruxox should return the charter. When this first request failed his requests turned to bullying “he ceased not to vex a certain priest until he resigned”. The canons eventually gave back the charter in return for a one off payment of forty shillings. Despite this the story did end happily - for the canons. Gilbert was “smitten with leprosy and lamentably confessed in the presence of the Archdeacon that he deservedly felt God’s chastisement, and there upon restored Ruxox to its former state”. Gilbert’s daughter, Osmunda, then married a William Fulcher and Flitwick was part of her dowry. By 1200 she, her husband and her mother had confirmed this donation.

The Cell of Ruxox and its Chapel of St Nicholas Although all these charters were preserved at the priory, we know very little about the founding of Ruxox and at this stage nothing about its connections with Dunstable. It appears that sometime before 1170 that the original donor, had founded a chantry chapel dedicated to St Nicholas, the patron saint of people travelling on the sea (pilgrims). Unusually this chapel had not been within or an extension of the parish church of St Peter. He must have had permission from the bishop to build a separate chapel with accommodation for several ordained ‘canons’ (clergyman). Not only was this independent of the village church but as we have seen ‘owned’ both village churches, Flitwick and Husborne. Osmunda’s gift for the souls of her father and late husband confirmed that they had given Ruxox and its possessions to Dunstable Priory. She requested that “divine office may be celebrated and religion preserved continually by honest men of Dunstable”. This grant was confirmed by their overlord, William, Count of Albemarle and the Countess Haweise .

The family continued to take an active interest in both Ruxox and Dunstable Priory. Two of Osmunda’s sons became canons at Ruxox and more gifts were given for their support. Other gifts were given so that departed members of the family could be entered on the prayer roll and that the canons would “make service of prayer for them yearly as for their own Brethren both at Dunstable and at Ruxox”. Things did not always run smoothly, charters were contested and not just the Bishop of Lincoln but even on occasions the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Pope were involved! However once things had settled down it became clear that Ruxox was a cell (small daughter house) of the priory rather than a grange or independent farm. Various officers of the cell are mentioned e.g. an almoner and sacristan. A list of officers during the reign of King Henry VIII also included a cellarer who would have been in charge of both their agriculture interests and their kitchens and food production, a hospitaller to care for their sick and elderly members and an almoner to care for poor people in their area and travelling through. Their sacristan would be in charge of the church building, and, the church services. The list also includes the farm bailiff and his assistant plus a herdsman. Gradually the estates of Ruxox and of Dunstable grew. In 1248 the priory paid for a new house to be built. It had a dining room and kitchen, a room for storing bread and beer and a dairy and there was a cellar where fresh food could be stored. All the canons at Ruxox had to provide was bread and beer for the builders. Once the dairy was finished they built a great barn.

The most valuable gifts that the prior had received were: a watermill and fishing rights, pasture for one hundred sheep and grazing for cattle. It must have been a terrible set back when rustlers, with bows and arrows stole 100 oxen recently branded and turned out on the moor. To get more help with their farming interests the priory paid for the freedom of some men tied to Flitwick Manor so that they could work for them at Ruxox. Once ordained, some young men chose to become resident canons at Ruxox. Two of them got Ruxox into trouble by night fishing in the water owned by the main manor. Older canons in Dunstable may have retired there and sick canons may have come for convalescence. It is possible in later years that after the regular ‘bloodletting’ (thought to improve health) some of the Dunstable canons may have come for a holiday as the St Alban’s monks did at Redbourn. In 1250, Prior William le Breton found the responsibilities of running an important house like Dunstable were too much for him and got seriously into debt. He accepted retirement and ended his life at Ruxox. So that his expenses were not a drain on the kitchens at Ruxox he was provided with 14 gallons of beer and 14 loaves of bread a week plus a small sum of money to pay for ‘his necessities’. Some of the bread and beer was probably used to feed the servant and stable boy sent to look after him. Seven years later he was buried with full honours in the Chapter House at Dunstable. However ten years later, Brother Stephen, the curate of Flitwick, died at Ruxox and was buried there “because of the stench”.

Although it is not known what happened to Ruxox during the last years of the priory, evidence suggests that it was an active cell well into the reign of King Henry VIII. It has its own entries in the Court of Augmentation records and there are references to “pasture” and “more” (land) and to the “manor” house but not the chapel. It has been suggested that the latter may have become a Chapel of Ease – or local chapel for people living in that part of Flitwick.

The Church of St Peter Flitwick No medieval references have been found to the double dedication of St Peter and St Paul. The medieval history of the church is invariably involved in the charters concerning Ruxox. When in 1220 the Bishop of Lincoln dedicated various churches on behalf of the priory he did not include Flitwick. However many years later, around 1280 the Archdeacon of Bedford, “on the mandate of Richard, Archbishop of Canterbury” and at the request of the family, inducted the priory “into corporal possession” of the church. This suggests that they were excused setting up vicarages and glebe land but were able to appoint canons from Ruxox and elsewhere. It even seems likely that the incumbent Thomas Marshall who was appointed in 1250 but then resigned was the man of the same name who was elected prior of Dunstable in 1251.

In the rent list of 1541/2 Flitwick rectory was included in the manor of Ruxox and no vicarage is mentioned. When this rent list was prepared for King Henry, the priory had already leased the land to a tenant back in 1537. The buildings, residential and others had been separately leased out as “a capital house or manor ……. called Rokesoxis”.

Husborne Crawley Although the entry at 1086 makes it clear that the present village was divided between two Norman owners they are both entered under Crawley. However a charter of 969 names the area bordering Aspley (Guise) as Husborne.(BHRS I) It is under this name that the church was given to Ruxox. This gift was confirmed by the overlords and by the Archdeacon of Bedford.

The Church of St Mary When they received the church the priory had to accept that it came with a vicar, who presumably had a small piece of land for his support. The Archdeacon was consulted and arranged that ‘Richard, Clerk of Husborne Church’ should resign the vicarage to the priory. They were then able to lease it back to him. Around 1204 he signed a second lease, for seven years. He is described as ‘chaplain’ and the arrangement was that he should receive “all the offerings and tithings”. However this was not quite true as there were some unspecified exceptions. Unlike Flitwick, Husborne did receive a perpetual vicarage in 1220. The family continued to take an interest in the church and soon afterwards added a second aisle and later a new porch. The new chancel front which they built is still in use today. In 1228 the annals include an intriguing story concerning the church yard, “On the day of St Stephen a treasure was found in Husborne church yard worth, about 50 marks (nearly £17). They then explain that they were obliged to hand it over to the Assize Judges, who sent it to King Henry III who donated it to a new hospital at Dover.

In advance of the dissolution, and maybe even making preparation for it on March 7th 1534 the prior Gervaise Markham leased the rectory with tithes and other income and profits but not the advowson to his brother, William Markham for 41 years. After the dissolution the rectory was taken over by the king and from the rectory rent of £21 6s 8d, £8 was set aside each year for the vicar.

The Manor of Crawley Over the years small pieces of land in Husborne were donated to the priory, but their really worthwhile estate was developed in Crawley. After 1066 this second half of today’s village had become part of the great estate owned by the Albini family at Cainhoe Castle. As the centuries went by their barony passed through daughters. Equally the descendents of the Sanvill’s of Flitwick became more difficult to identify. The Nicholas Tingrith who became a generous benefactor of the priory was a relation of the Sanvills. He confirmed some of their gifts to Ruxox. Early in the 13th century in his own right he gave them small pieces of land near their ‘marl pit’ and also tithes of hay in Husborne and tithes from a watermill at Crawley. He encouraged his tenants to make gifts and one of these lay beside the prior’s ‘sheepfold’. A tenant of the priory was renting two ‘houses’ and small accompanying farm yards which the priory owned. From all of this it can be seen that the priory was building a worthwhile estate at Crawley.

In the mid 13th century, maybe towards the end of his life, Nicholas Tingrith became a friend of the priory and in return gave them both his manor of Crawley and, the secular manor of Husborne. He also added to the land that they already held in Crawley. Wanting to raise as much income as possible for the social work that they were doing in Dunstable they set out to really develop their assets. In 1250 they built a byre for their cattle and a pigeon house. Then continuing to build with the idea of producing an independent grange, which would greatly add to their income, they enlarged the sheepfold and put up three new buildings for washing wool. Then they built another cattle shed.

By the time of the dissolution the priory appears to have parted with this prosperous grange. In 1534, William Markham had rented the Manor of Crawley along with the Rectory of Husborne. Amongst the list of property already handed over to the king in 1542, Husborne Crawley was recorded as part of the Lordship of Brogborough.

The Church of St Mary, Studham and the Manor of Barwythe

Barwythe lays to the south of Studham and Humbershoe is a small separate piece of land now part of Markyate. Studham and Barwythe were, until 1897 divided by the county boundary and so had two separate entries in the Domesday Book although both were held by the Tosny family of Belvoir Castle. Their vast scattered estates were soon to be divided between daughters, represented by their husbands and so the name of the overlords who confirmed the various grants changed. By 1100 their tenants were referred to as ‘de [of] Studham’.

One of Bedfordshire’s rare Saxon documents records that Oswulf and his wife Adelitha, having entered the brotherhood (became lay members) of St Albans Abbey made a gift of twenty shillings for charity “……… and offered to God and to his holy martyr St Alban in great devoutness the land which is called Studham”. They made this gift “……. for the souls of themselves and all their kin”. Oswulf owned the manor of Miswell and had land in several villages around Tring. Adelitha had inherited Studham from her first husband Ulf and they added to their gift a request that regular prayers should be made for his soul. They then clarified the position; they would keep the land of Studham during their lifetime paying twenty shillings a year for it, towards ‘the feeding of the monks’. The date of this gift is uncertain but thought to be well before 1066. The Domesday Book doesn’t mention ownership by St Albans Abbey; Studham and its hamlets were all included in the estates of the Tosny family. The deed recording this gift included a request that the Abbot of St Albans should “……. give them timber to build in that vill[age] a church in honour of Our Lord Jesus Christ and of St Alban ………”. Had this wooden church been built, as one of group of buildings around the manor house, it would not have shown up in the Domesday Book – not having any separate land set aside for its support. However, at Barwythe a priest is listed amongst the other estate workers. The fact that Robert Tosny founded, a Benedictine Priory, as a cell of St Albans Abbey, next to his new castle of Belvoir may have been to ward off the “fearsome curse” which the bishop had added should anyone interfere with the grant to St Albans Abbey.

The Church of St Mary Part of the rent for the tenants of Studham was to supply officers to help staff the castle. By the end of the 12th century William of Studham was an officer at the castle and his brother Alexander was running their estate. It was Alexander who well before 1180 gave Studham Church to Dunstable Priory. The embarrassment was that Alexander’s youngest son John was taking the church services and held the piece of glebe land, and he had a wife and children! Alexander made every effort to get legal confirmation of his gift but it took some years to settle family disputes. His son’s William and Robert confirmed it from the beginning; as did their overlords. The Archdeacon of Bedford wrote that he had accepted the prior “…….. to the Rule of the church to the honour of the Blessed Mary in Studham, and had inducted him as parson --------at the request and with the approval of John Clericus son of the aforesaid Alexander”. The Bishop of Lincoln was consulted and he inspected and confirmed the charters of both Alexander and the Archdeacon but still there was no personal confirmation from John. Somebody had asked King Henry II to give his official approval and as early as 1179 he wrote to the Archdeacon from Windsor giving his approval to the fact that Dunstable Priory now ‘owned’ Studham Church. The matter would appear to have been settled when in 1202 ‘William of Studham’ visited Dunstable and agreed to add the advowson of the church to the previous gifts in return for 5 marks of silver and an expensive riding horse. This William was probably husband of John’s niece Marjorie. His eldest brother Robert had four daughters and two young sons; Marjorie the eldest daughter had married William Eltendon. He would take over the manor at Studham and at a later date made several gifts to the priory. In later years his son became vicar. However what none of these confirmations allowed for was that John had three sons and they had grown up knowing that their grandfather’s [Alexander] gift to support their father in his work would one day be their inheritance. Now they saw it being snatched away from them and they and their mother would be homeless or at best, tenants of what they considered to be their own property.

Eventually the whole matter was taken to the pope for his final judgement. The pope asked the Abbot of Waltham and other senior churchmen to set up a panel of enquiry. They heard evidence from both sides and the Charters record that in 1204 John formally “renounced his rights to the church of Studham”. They also noted that the priory definitely owned half of the tithes and half of the church land. The full report was much longer and the grants for around 1204 are undoubtedly connected. On the one hand the family made gifts to the priory e.g. John’s son, Adam gave them the land adjoining his father’s house except the house where he and his brother Ralph lived. His son Roger, granted land in Barwythe. On the other hand the priory felt they should give some support to John’s wife and children. John’s son, Adam followed by his brother Ralph could have all the land which belonged to the church, for the low rent of ½ mark each year. Following their deaths it would revert to the priory, this was because of help they had given the priory and “the benefactions made by his family”. This joint gift would protect their mother who was also involved in the transactions receiving in her own right 10 acres of land in Studham in return for 7 acres elsewhere; maybe part of her dowry. John lived on until 1212. Not only were his sons and son-in-law generous to the priory but there were numerous gifts from their tenants. The priory soon gained large and small gifts in Studham, Barwythe and Humbershoe. As in some other places they made exchanges of land and were able to put together a valuable grange farm suitable to lease out at a good rent. In 1249 they built a sheepfold and improved the cow sheds, in 1253 they added a dovecote followed by a new barn.

Once they were certain of owning Studham Church the prior, maybe helped by the landowners set out to build a new, stone church; much of this can be seen today. The basic work was probably completed by 1220 because when the Bishop of Lismore was visiting Dunstable he dedicated the church and its five altars. He also consecrated an enclosed churchyard. The entry in the annals ends with the statement that when his dedication was completed he added “……. an annual remission of twenty days”. This wording of remission who were worried about their earthly sins should visit this new church and pray for forgiveness they would receive twenty days off their penitential period in purgatory. There is a note in the annals referring to the fact that in1275 the Lord of the Manor had renewed his moat and that it now ran “towards the cross”. The remains of the moat are still visible at Church Farm and is within one hundred yards of the east end of the church. This suggests that at one time there was a preaching cross just inside the churchyard. In October of the same year when the new Bishop of Lincoln visited Dunstable to check that the priory had provided each of their churches with a vicarage and land. The priory noted that the bishop had looked into the subject very carefully to make sure that they would be properly funded, and just in case things went wrong all his records were stored in his ‘bookcases’ at Lincoln. The glebe, that is the main land set aside to support the vicar was 7 acres known as ‘Vivian’ which was later described as “on the left hand going out of the village towards Dunstable and remained part of the endowment of the vicarage until a few years ago”. There was then an exchange with the Ashridge Estate. Part of these seven acres today, are probably represented by Bell farm, better known as the popular Harpers Countryside Retailing. The priory must have been grateful to Bishop Hugh for keeping these records. Sometime before 1250 a later bishop raised the vicar’s stipend which the priory paid for the first year or two but then went back to the amount set by Bishop Hugh. Then Walter the vicar complained bitterly and the Abbot of Westminster was asked to arbitrate. Having heard the evidence put forward by the priory, to the disappointment of Walter, he confirmed that the priory could continue with the original stipend. The years went by and different vicars came and went. The priory used their land at Studham both to produce food and money from rents; the farmers at Studham had a reliable market for their produce in the town of Dunstable and at the priory.

The Manor of Barwythe The Eltendon family who had chosen Barwythe as their manor house continued to support them. They had their own chapel at Barwythe and in 1236 the priory allowed William Eltendon to have a chantry in this chapel. The Bishop of Lincoln agreed, provided he gave compensation to the priory to make up for lost income at St Mary’s Church. At this point it is possible that the priory were a little too greedy in their demands. Over and above the compensation ordered by the bishop Eltendon apparently gave them quite willingly an extra 5 acres of land. However the entry of this second gift is followed by the fact that William got extremely angry and Simon his tenant brought summons against thirty nine of the priory staff for ‘breach of the peace’. The Assize Judge was consulted and ruled in favour of the priory. This disagreement must have settled down quite quickly because soon afterwards William’s son Roger became vicar of St Mary’s Church.

In 1528 the priory drew up a lease for a 70 year term so that William Belfeld could hold the Manor of Studham and its rectory; he was a tenant of the king in 1542. In 1536 he was also able to lease the rectory and in 1541 the officers at Ampthill had drawn up a new 30 year lease. The original agreement covered not only ploughland, woods and coppices (farmed woodland) but also “all barns both roofed with straw and another great barn ……..” and most of the tithes but not those of Humbershoe. As a cash crop some pieces of land must have been used for growing peas because he had to add to his rent 6 measures of green peas. Despite what appear to be constant disputes the families holding Studham and its hamlets must have welcomed the Augustinian priory on their doorstep. The constant prayer life and worship at the priory was a wonderful support for their own spiritual lives and consciences. In addition they must have known that their frequent gifts were helping the canons pay for these social responsibilities supporting poor, sick and disabled travellers.

The Church Of St Mary In October 1220 the Bishop of Lincoln included Studham in the group of churches where he instituted ‘perpetual vicars’ i.e. insisted there should be a resident vicar. A resident vicar who was to have a glebe of about 7 acres and was to receive all the payments connected with family services, and a tithe of lambs.

The Church of St Mary the Virgin, Harlington and The Church of St James the Apostle, Pulloxhill

Although Nigel of Aubigny (later Albini), was the Norman baron in charge of administration in mid Bedfordshire and held thirty villages or parts of villages in this county, he held very little land elsewhere. He had a castle, the earthworks of which remain at Cainhoe, near Clophill. Three of what proved to be valuable grants to the priory were Harlington Church, Pulloxhill and the Crawley side of Husborne Crawley were owned by Nigel and his family. They were all great supporters of St Albans Abbey and a relative; Richard of Albini became abbot in 1197. Nevertheless they and their descendents were only too happy to support grants to Dunstable Priory.

They kept this prosperous well populated village of Harlington for their own use; probably to help supply food for the castle. Apart from the ploughland and meadow they also had woodland for 400 pigs. A small part of the woodland had been cleared and each year their farm manager had to send a pack load of oats to the castle probably to help feed their horses. In 1086 their tenant at both Streatley and Wyboston was one of their officers simply referred to as ‘Pyrot’. This was probably the same man who held small pieces of land at Beeston and Northill from another Norman land holder. He must have been recognised as an officer with a useful future because by the early 1170s his family had become the Albini tenants at Harlington with the status of lords of the manor. The ‘charters’ were records kept by the canons at the priory, they were not filed in date order and often dating has been left to G. H. Fowler, editor of BHRS Vol. X . Their charters concerning Harlington and Pulloxhill Churches are very confused and could be inaccurate.

Sometime before 1181, Ralph Pyrot and his wife Matilda had granted Harlington Church to the priory. The reason for the grant was a request that Ralph and his wife might “……… be received as brother and sister [of the priory] and partakers of all benefits in life and death”. Today we might say ‘put on a prayer list to receive regular prayers for their physical and spiritual health and welfare’. They would also expect the canons to arrange and carry out their funerals. What happened to Matilda Pyrot has not been recorded but in 1195 Ralph had became a monk at the Cistercian abbey of Woburn. In 1223 their son Richard, added the advowson to their gift. This grant went ahead but as so often happened with these early grants, it turned out there was already a vicar in charge of the church, which in this case was ‘Phillip the Clerk’, who insisted that the Pyrot family had already given it to him. The charters record that when the Archdeacon of Bedford was asked to confirm the gift – he admitted that Ralph Pyrot was “…….admittedly lord of the fee of the church of Harlington” but added that Phillip should hold it for his life and pay the priory two shillings a year as rent. However amongst the list of complaints that the priory sent to the pope, around 1200, was the fact that Ralph Pyrot and the Archdeacon of Bedford did not support him in his choice of a vicar for Harlington church. The pope’s representatives, the Bishop of Lincoln and other important church officers found in favour of the priory. Everything must have been running smoothly by 1200 as Harlington was not a vicarage that the Bishops of Lincoln found necessary to establish.

The priory hung on to the church and the land which went with it and well before the dissolution had also obtained ownership of the Manor of Harlington. Some years before the dissolution, the priory leased the rectory and tithes for a money rent. The Victorian writers have named the tenant as William Belfeld but the rent list, compiled for the Court of Augmentation in 1541 name Anthony Stubbings. He was a relative of the prior and incidentally rent collector for the Court. The original lease was in 1535 but on the eve of the dissolution it was rewritten for sixty years. By 1542 it had been transferred to the offices of the Court at Ampthill.

Over the years the priory rebuilt part of the original church and gradually added to it. Today it has Grade 1 status because of its unspoilt medieval features.

Pulloxhill The grants of churches or manors did not always run smoothly. The desire to gain spiritual benefit was obviously very important and most of a tenant’s gifts to the priory were automatically backed by the main holder of the land. Competition between the main land holder and their tenant could cause problems and it was not unknown for dutiful sons to confirm a gift in the lifetime of their parents, to regret it after their death and to try and cancel it. When the church or agricultural manor was divided between two daughters it could lead to two competing sons-in-law and this could cause even more problems. Competing religious houses were not common in Bedfordshire but caused the priory problems in Buckinghamshire.

The Domesday report in 1086 showed that this was another well populated and useful agricultural village. The Albini family used it to help support two of their officers Roger and Rhiwallon. It had suffered when the Norman army passed through but was already recovering. Evidence from later tax reports indicate that both the population and the success of its agriculture continued to progress quite rapidly. By around 1100 the tenant of the Albini family was the Buignon family. They held it by right of Ralph’s wife who had inherited it from her father. It appears that the church had been bequeathed to his two daughters and the other had married John Pyrot of Harlington.

The Church of St James Few gifts to the priory can have been more complicated than that of the church at Pulloxhill. Both sons-in-law claimed a share of the church and the Albini family not only confirmed the various grants but at times claimed their own right to grant it to the priory. The charter dates are also confused but it appears that sometime before 1176 the main lord, Robert of Albini granted the church to the priory because he and his heirs were to be received into the benefits of the church. Then a few years later; presumably as co-owners of the church under the Albini family, John Pyrot and his wife Agnes also made the same gift as tenants of their half of the church and their son Simon added the advowson. This was because, not only had the canons received him into their brotherhood but they had undertaken to make him a canon in his lifetime. Before 1181 The Archdeacon of Bedford announced that, he supported the grant of Robert Albini and had legally instituted the prior as parson (the equivalent of the rector). This was to the Archdeacon’s satisfaction; because Albini had proved his right to make the grant. Enquiries must have gone even higher because the Bishop of Lincoln then announced that he confirmed the priory’s ownership of half of the church. Then confusion came from a similar grant by the Buignon family. 1210 Henry Buignon granted that half of the church “which belonged to him and his ancestors”. This would appear to settle the previous disagreements except that Simon Pyrot then confirmed the grant of the church which his father had made, followed by another grant of the whole church by Simon’s son William, this time including the tithes and Robert Albini confirmed his father’s grant.

Some of this confusion may be due to the slackness of the priory clerks but the annals make clear that there were bitter struggles. In 1210 Henry Buignon took them to the king’s court demanding half of the revenues of the church. They won this lease and the more serious case in 1260 when William Pyrot took them to court concerning the right to present the vicar to the church. Pyrot paid a highly respected lawyer but the prior appears to have won the case on the grounds that Pyrot’s only claim to the church was through the wife of his grandfather! The trouble really started when an even more serious claim was made by the Abbess of Elstow. Backed by the Bishop of Ely on behalf of the pope she proved that she had previously been given the churches of both Pulloxhill and Flitton. There was what the clerk described as “a long controversy” before the priory surrendered any rights they held in Flitton church and agreed to pay an annual rent of ten shillings for Pulloxhill. This was a very large sum of money and it may be the reason why in the 16th century the church was frequently reported as being in a bad state of repair. The next claim by Abbot of St Nicholas of Anjou was nothing like as serious. He claimed that Peter Buignon had previously given him the tithes. That was settled by an annual payment of two shillings. Despite all these problems the life of the church ran smoothly. In 1205 the Bishop of Lincoln instituted a vicarage and in 1220 his assistant, the Bishop of Lismore dedicated the church in honour of St James.

The Manor of Pulloxhill The priory’s land holdings prospered over the years both the Pyrot and Buignon families made a series of agricultural grants and other small grants were made by their tenants. The value of these gifts to the priory can be judged by their variety; ploughland, meadow, grazing, marshland and enclosed pieces of woodland. The sizes of these gifts varied, one gift of land in the west field was assessed as 26 acres, another much smaller, being part of an enclosed area was marked out “by the view of good men ……. by a stone fixed in the ground and an elder tree in the hedge”. By making careful exchanges they were able to link some of these small gifts together. They were given farm houses and cottages and a share in the water mills at Greenfield and Flitton. The annals record that in the 1250s they built a big barn and enlarged the cattle shed. By spending money on their scattered estate they were able to let out separate farms to tenants. Back in 1229 they had leased a messuage (farm house and buildings) and some land adjoining it to William Syaph and his wife for 4 shillings a year. If one of them died the normal death dues of their ‘best beast’ would go to the canons; when the partner died their farm would revert to the canons.

The Bishop’s visitor in 1518 and in 1530 reported that the church was in a bad state of repair. [A series of repairs took place and in 1845/6 there was a partial rebuild.] However much of the church from the days of the priory still remain. Recorded within the 1542 rent list is a lease which the priory made out in 1527 leasing the Manor of Pulloxhill to Thomas Wye. With the house came valuable agricultural land and the right to hold the manor court. The tithe barn was not included nor some of the valuable woodland. Out of his income Wye had to pay the vicar ten shillings per year. In 1531 this lease had been extended for another sixteen years. Two years later they drew up another lease allowing him to rent the rectory with its tithes and tithe barn; this was then increased for another seven years. The officers at Ampthill decided that these leases could stand but they increased the payment to the vicar and added a fee of twelve shillings to the sheriff. A later clerk “extinguished” the fee to the sheriff and the money went to the king. By the end of 1542 both manor and rectory had been transferred to the king.

Not in this rent list but in later records, Canon Richard Kent, once of Dunstable Priory was in 1548 “living in Pulloxhill” and from 1540 until he died in 1554 was vicar of St James. Shortly before the signing of the dissolution the prior’s brother, William Markham, gentleman of Pulloxhill, Adam Hilton of the Saracens Head, who managed Dunstable for the priory (and would later manage it for the king) and Thomas Kent of Luton (brother of Canon Kent) obtained the advowson – and so Canon Kent got the living! It was a very humble position but in 1553 he was able to add the rectory at Higham Gobion. He died the following year and Dunstable’s connection with the Church of St James came to an end. Baskerville G. English Monks and the Suppression of the Monasteries 1937

The Manor of Wadelow’s [Toddington]

Wadelow’s bordering on Harlington is best identified today as adjoining Poplars Garden Centre, who have developed a piece of land as a Nature Reserve.

Just after 1203 the manor of Toddington was held from the king by William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke and two of his tenants were the Pever family and the Wadelow family. However early on in the story Paul Pever was allowed to take on the role of Lord of the Manor at Toddington while John Wadelow continued as a tenant farmer. When around the year 1200 he gained an assart (cleared and ploughed piece of woodland) it was described as “adjacent to his land at Wadelow”, so there was land referred to as Wadelow’s before 1200. It may be that his family name came from this low laying piece of land. Later he gained land at Chalton and a little at Fancott.

However as the years went by Toddington’s peaceful farming community would soon become disturbed by the struggle for Magna Carta. The absentee King Richard died abroad in 1199 and his brother John came to the throne. Paul Pever left Toddington to become a respected officer for William de Cantilupe of Eaton Bray. It was probably Cantilupe who introduced him to King John’s court where he rose to hold several senior positions.

At one stage he was described as a “special councillor”. The money that he made by these ventures he invested in land, in Bedfordshire and elsewhere. Matthew Paris, the chronicler at St Albans Abbey, recorded rather sarcastically that when Pever went to court he held less than 250 acres of land but “by means, lawful or unlawful” he soon became possessed of around 14,000 acres! Disagreements during the reign of King John led to the fight for Magna Carta. As Paul Pever relied on his overlord, William Marshall for the position and lands that he held in Toddington and the same William Marshall was the main supporter of King John it is not surprising to find Pever fighting on the side of the king. John Wadelow was also on the side of the king but in a quite different role.

Fawkes de Breauté, a mercenary, who was extremely supportive of King John throughout the civil war became sheriff of Bedford Castle. At some stage he recruited Wadelow as steward of his scattered lands. Unfortunately when King John died in 1199 and those who fought against him agreed to support the young King Henry, Fawkes refused to give up Bedford Castle. He terrorised the people of Bedfordshire and went so far as to build a second small castle in Luton, where his soldiers caused great damage. In brief, by 1223 when law and order had been restored a group of Lutonians took de Breauté to the Assize Court, first at Bedford, then at Dunstable. It was the summer of 1224 when things came to a head. Having retreated to the Welsh border, de Breauté sent his brother to kidnap the judges as they sat trying his case in Dunstable Priory. One judge was captured and put into the dungeon at Bedford Castle, causing the young King Henry III to besiege the castle. The men of Dunstable were given the (doubtful) honour of breaking the siege and, what is considered as one of the best descriptions of the breaking of a siege is included in the Dunstable Annals. This drama ended with first the ceremonial hanging of de Breauté’s brother and all the other soldiers and then the capture and return of de Breauté himself. He was then sent into exile and died abroad.

So what happened to John Wadelow? At the end of the siege, following the hanging of the soldiers, the annals record “Thus all the men Fawkes had in England dispersed without moveable or immoveable goods”. Not being a soldier Wadelow is probably included in this group, although he did not “disperse” out of Bedfordshire.

Up until 1224 there are no priory charters involving Wadelow’s, in the following years there are over forty. What is uncovered must be one of the most unusual reasons for making gifts to a religious house that has ever been recorded. It is possible that as sheriff, Fawkes added to the land which Wadelow held, both in Toddington and Chalton and maybe arranged with Pever that he could make a separate manor of his land at Wadelow; this maybe the origin of the title Manor of Wadelow. Whatever the situation the new sheriff gave instructions that all Wadelow’s property and goods of any kind should be seized and then sold and it appears that this actually took place. In panic Wadelow personally appealed to King Henry III. We do not know what sums were involved but Henry agreed that he could have everything back if he raised a very large ransom. It was for this reason that he gave up all his lands, buildings and the rights which he had in the hamlet of Wadelow to the Priory. The charters are far from clear concerning these transactions but it seems that at one point they gave him 10 marks (£3 6s 8d). In addition he granted them his land in West Worthing, adjoining Flitton, at a rent of 5 shillings. Also at this date he appealed to the priory to care for the “redemption of his soul” (regular prayers to help him through purgatory) and added ¼ acre of land for that purpose. So concerned was he for the future care of his wife that he even handed over her dowry. In return, in the event of his death, they would provide her with a house, her food and other necessities and a respectful funeral for a lady of her social class.

The rush of charters suggests that he also added several smaller gifts of his agricultural land. Apart from appealing for help from the priory it appears he may also have turned to Richard Pyrot of Harlington. In 1227 he summoned Pyrot to the assize court and claimed 375 acres of land. However to add to the general confusion Pyrot died before the judgement and no more is heard of this Harlington land. Interesting details came out of this rush of gifts e.g. the description of a long piece of dyke and the quick (blackthorn) hedge beside it, plus the willow trees which had been planted alongside. Also 4½ acres of meadow lying alongside of a stream which the canons could enclose if they wished or plough up for arable. So desperate was he for ransom money that he added his interest in the barley mill at Flitton and not only his land at Chalton and West Worthing but also at Pulloxhill. At one point the homestead at Wadelow is described as “abutting on the road to Wood End (Harlington?) This key selection of charters shows that the Wadelow family holdings had grown during John’s lifetime. Just what he received for all of this is not clearly stated. In addition to the £10 there are several references to gifts of 10 marks. Maybe the prior paid all or part of his ransom direct to the king? There is also a reference to him receiving “necessities” which probably meant “board and lodging”.

An entry in the Dunstable annals for 1232, possibly the year of John Wadelow’s death, would appear to clarify the whole position “----- we received full possession of the whole land of Wadelow with its payments of homage, its demesnes [manorial rights] and services performed”, confident of their legal ownership the priory built a fine new house there. However it wasn’t that straightforward. Two years later John’s son and heir Hugo granted to Paul Pever all his land at Wadelow and Toddington in return for a corrody and 10 shillings yearly. The priory challenged this gift and Pever surrendered Hugh’s charter, in return for 5 marks and 5 quarters of wheat, a small piece of land and the assart in Northwood. As this had failed Hugo then approached the priory for the corrody paid for by his father and was promised the same food and care as would be given to one of their own canons plus 10 shillings a year. This was confirmed at the King’s Court.

Despite legal challenges from the Pever family and others the priory continued to develop their valuable estate. The separate story of the Pever Family at Wadelow and their “palatial” house that they built there adds to the confusion of the priory’s manor. Their new house was burnt down but was soon replaced and they put up more buildings and, when possible bought more land. The value of the estate in supporting their work in Dunstable was recognised by King Edward II and in 1323 he granted them free warren – that is the right to keep for their own use and catch as needed all sorts of game. Also they managed to get extremely valuable fish ponds originally dug out by the Pever family.

In 1533 the priory leased the Manor of Wadelow for twenty one years with all its agricultural lands, but not its manorial rights or the rights to fishing, fowling or hunting. It went to a gentleman called Thomas Coke, he was to pay rent of £4 13s 4d each year. However within a few years of the dissolution the whole manor belonged to the King.

The Church of St Giles, Totternhoe, and the Manor of Shortgrove. The Church of All Saints Segenhoe and The Manors of Ridgmont and Brogborough

Following 1066 there were some families who were dependent on the Norman kings for the comfortable position that they held in England. A family of Flemish mercenaries who took the name Wahull from the village where they built their castle (Odell) had administrative responsibilities in North Bedfordshire and part of Northamptonshire. They were responsible for providing armed watchtowers on high points around the county such at Totternhoe and Segenhoe. Their duties also included a share of providing armed support in Rockingham Castle. To help pay for all of this they also had smaller estates in two other counties.

In the Domesday record of 1086 there had been two brothers, Sihere and Walter and also Sihere’s two sons, but Sihere had recently died. By 1131 when King Henry I had given the priory and the whole town of Dunstable plus land in surrounding villages and the royal stone quarry at Totternhoe it was Sihere’s grandson who held part of Totternhoe. He was responsible for the ‘castle’ overlooking both the stone quarry and Henry’s new business centre on Dunstable crossroads. Two of the earliest charters dated soon after 1131 are when Simon and his son Walter notify the Bishop of Lincoln their wish to give their church of St Giles, Totternhoe to the priory and a separate charter when Simon and his wife Sybil and again son Walter gave the church at Segenhoe. There were several more charters to come but no real disputes and Dunstable Priory held these two churches to the dissolution. At first the priory supplied canons to take the services but in 1220 the Bishop of Lincoln endowed vicarages at both churches making sure that not just a house but also various sources of income had been provided.

The Church of St Giles The Bishop found that this vicar should receive the ‘altar – offerings (money for family services e.g. baptisms) a regular small rent charge and part of the tithes. Later landowners appear to have worked alongside the priory to keep St Giles in a good state of repair and when necessary enlarge or rebuild. The Ashwell family carried out a great deal of work in the early 16th century; they have left their ‘mark’ in a series of carved shields illustrating an ash tree and a well. Much of this beautiful church today is as it was in 1541 when a William Belfeld was lucky enough to have his lease renewed by the officers at Ampthill. Five years earlier the priory had given him a 3d year lease which had included thatched barns and a ‘great barn’ which was probably to hold his tithes. In addition to money his rent included six measures of green peas. He also appears to have been allowed to continue with the lease which the priory made out in 1528 for the Manor of Totternhoe but there are few details and it may refer to part of the manorial land.

Shortgrove Most of the land north of Totternhoe church was in separate ownership – but Simon’s land, south of the church went up over the downs and included part of what is now Whipsnade. That area became known as Shortgrove and the Wahull family leased it to two of their key supporters from Northamptonshire. These two men William Landas and Stephen Walton, got permission to give land to the priory; what became the separate manor of Shortgrove. This proved to be a most valuable gift; the ploughland, the down land grazing and the woodland at the top of the hill were well worth investment by the priory. In 1253 they built a grange (independent farmyard) and a dovecote and then a new barn. They were probably preparing to let it out to a private farmer in return for a high rent.

The Manor of Shortgrove Centuries later, knowing that they would soon be dissolved, the last prior of Dunstable made plans in advance. In September 1537 he leased to a relative, Anthony Stubbings the ‘Manor’ of Shortgrove with land, woodland, pasture, herbage, meadow and 5 acres of downland. He had originally held all the manorial rights but by 1541they had been annexed to the King’s Honour of Ampthill. The accountant at Ampthill continued to pay the vicar Thomas Lovell, as the priory had been doing £4 6s 8d towards his income

The following year they leased the Totternhoe tithes of sheaves, grain and hay to a Robert Pascall except for the tithes of grain and sheaves from Shortgrove. Tithes had always caused distress; good or bad years every person had to hand over a tenth of what they had grown. Quite early on the prior accepted a set annual fee instead of the tithes of hay.

Not only were there woods, pasture and meadow but also 5 acres on Totternhoe Downs and 5 acres in Studham fields. The Rectory of Totternhoe appears to have gone straight to the king. There was a house next to the rectory with 16 acres of land and 5 acres at the foot of the Downs.

The Church of all Saints, Segenhoe and the Manors of Ridgmont and Brogborough

The Wahull families’ responsibility at Segenhoe was to construct and man a defended watch tower as they did at Totternhoe. The Saxon name ‘hoe’ suggests a steep hill with a sudden quite sharp drop on one side. Whereas in most places the new Norman landowners retained the old Saxon names here they referred to their estate as Rouge-Mont, which soon became ‘Ridgmont’.

The first Norman owner was the late Sihere’s brother Walter, he kept it as a home farm to help provide food for the castle. It was a very useful estate having both ploughland and profitable woodland. Not only were they able to support 300 pigs but the woods also supplied timber and in the clearings they were able to rear rams. Each year they supplied 10 rams for the use of the Wahull’s other estates. The clerks compiling the national ‘Domesday’ tax report had less than a year to collect, collate and write out their material. This was maybe why in most places in Bedfordshire they did not record the number of sheep that they kept; they only recorded rams which were produced for breeding.

Walter had died childless and when the church was given to the priory Segenhoe like Totternhoe was in the hands of his great nephew Simon. Simon’s son Walter added his name to the charter and it was approved by both the Archdeacon of Bedford and the Bishop of Lincoln. The names Segenhoe and Ridgmont both occur in the various charters although the present church of Ridgmont was not built until 1854. A third name which also occurs is Brogborough which became part of the parish of Segenhoe/ Ridgmont. This site is not recorded as one of the watchtowers set up and manned by the Wahull family but when a list of taxes was drawn up in the early 1200s it included 3d for the priory’s fee towards the costs of running Rockingham Castle and 4½ d for Brogborough plus an extra 3s 2½d as ‘scutage’ in lieu of military service there.